This week, I’m sharing something a little different. A few weeks ago I did a workshop where I learned a new method for taking notes. The instructor, Andrew James from the Predator Free New Zealand Trust, encouraged us to use both words and illustrations, regardless of our artistic ability. He gave us a few tips on drawing and told us to have a go. Although my drawing skills leave a lot to be desired, I found the method fun, and I realised that with some practice I might be able to produce diagrams to accompany some of my articles.

In the coming weeks, I’m going to share some of my early efforts. As you’ll see, they are a long way from works of art, but that’s not the point. I’m trying to have some fun and make the information I’m sharing more accessible. This week, I’m explaining an initiative called One Health, as well as looking at what is going on with bird flu. I hope you enjoy following my progress as I practice my skills.

On the Tuesday and Wednesday of last week, I spent a couple of days attending a fascinating conference. If it hadn’t been on in Wellington, I wouldn’t have gone, but since it was local it was a great opportunity. I had been keeping an eye on it, and when the programme came out, I saw that there were a number of topics I hoped to write about. So, I decided to register.

The conference was the annual symposium organised by a group called One Health Aotearoa. If you haven’t come across the concept of One Health before, it may not be obvious what it is. But it’s exactly the kind of group which science, and the world, needs.

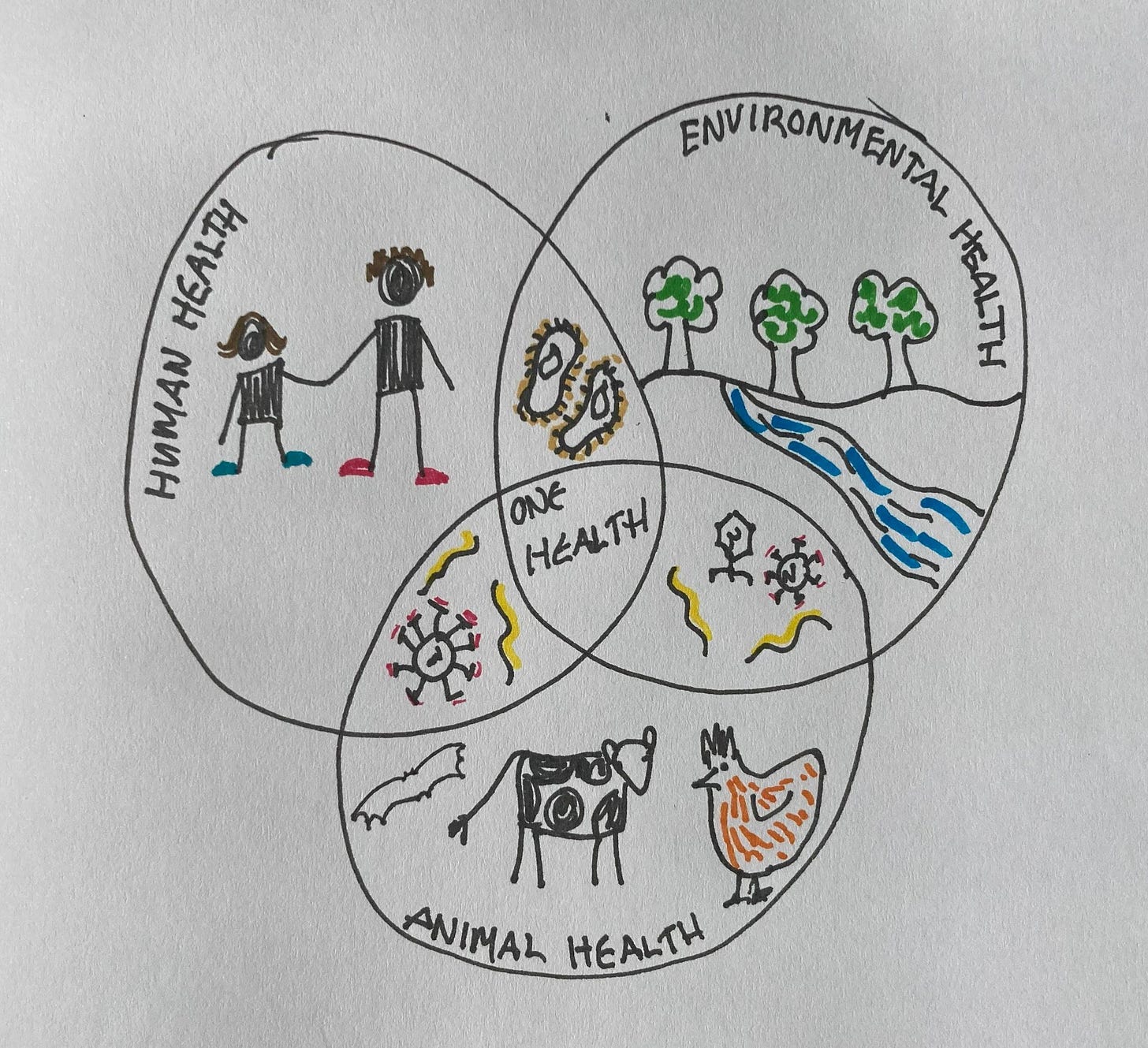

One Health is a global initiative which was prompted by a 2006 article by Laura H. Kahn, a doctor with particular expertise in diseases which move between animals and humans. These deseases are known as zoonoses. She highlighted the need for medical doctors and veterinarians to work together more closely to manage diseases which move between animals and humans. The resulting initiative recognises that human health, animal health and environmental health are all connected. There are now organisations connected with One Health around the world – in India, Europe, Africa, the Americas and, of course, here in New Zealand.

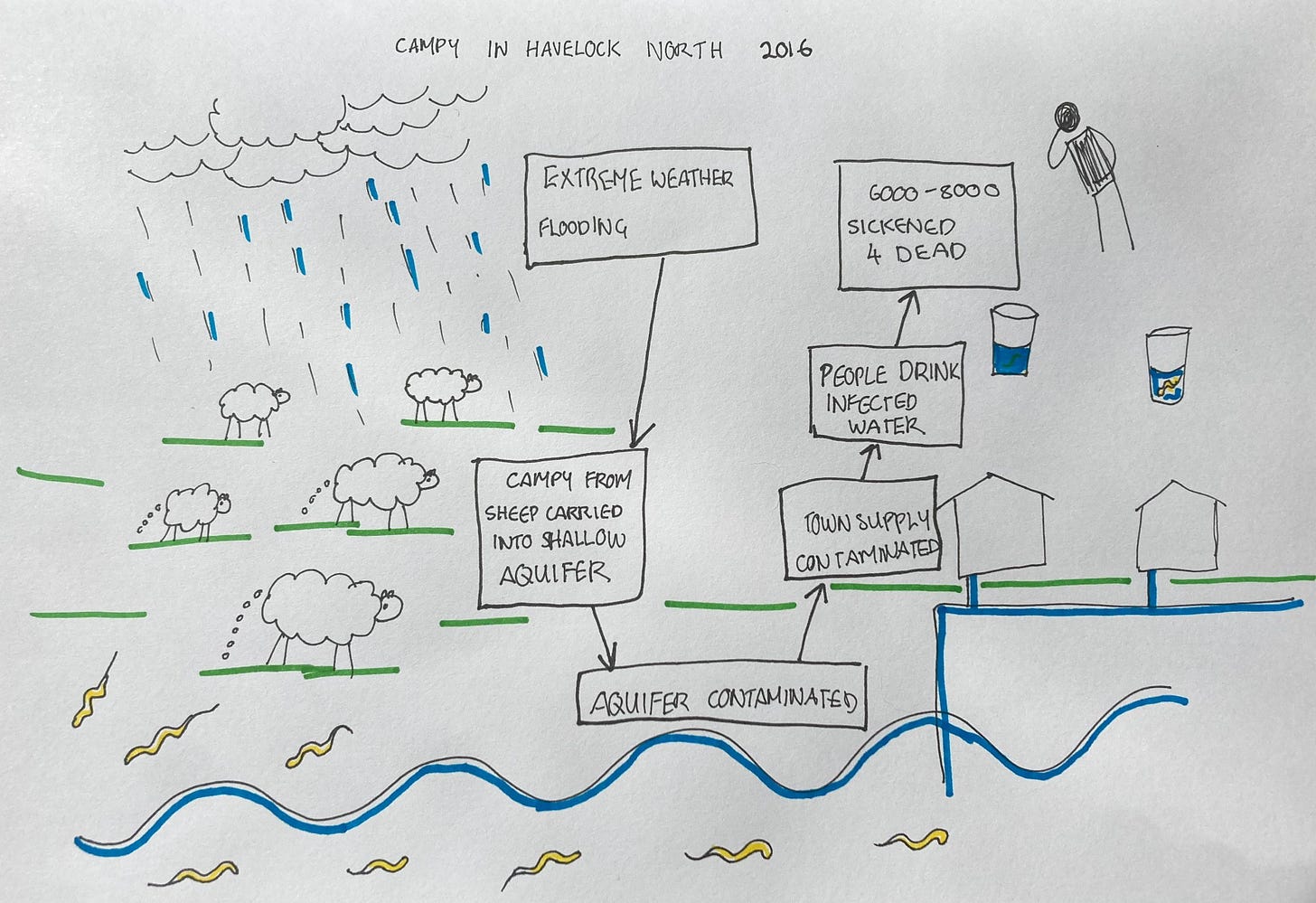

A good example to demonstrate One Health is the outbreak of disease caused by contaminated water in Havelock North in 2016. The disease was caused by a kind of bacteria known as Campylobacter, campy for short. An estimated 6000-8000 people were sickened and there were 4 deaths where campy was a contributing factor.

One of the topics on the agenda for the One Health symposium, which I was particularly keen to hear about, was avian influenza, otherwise known as bird flu. I’ve been planning to write an update for a while, so I thought that the symposium would be a good opportunity to learn more and meet some of the people who know the most about it in New Zealand.

The timing couldn’t have been better if I’d planned it. The day before the symposium began, New Zealand had a worrying report of bird flu in North Otago. Everyone at the symposium was talking about it. I was perfectly placed to learn more about where the outbreak came from and what it meant.

I last looked at bird flu in April of 2023, when I wrote about its history and spread. However, a lot has changed since then. Most of what I’ve covered here is different from what I wrote about last year, so it’s worth looking at the previous article for more background into the impact on wild birds.

As the name suggests, bird flu is a type of flu, or influenza. More specifically, it’s caused by one type of flu virus, known as Influenza A, which is the most important and most diverse of the flu viruses. There are two other types of flu virus which affect people and another which affects mostly cattle, but none of them cause pandemics, so I’m not going to talk further about them here.

Influenza A is primarily a disease of wild aquatic birds, and many of them, such as ducks and geese, seldom show symptoms. However, it is also known to infect humans, cats, chickens, whales, pigs, horses, bats and many other species. Influenza A is responsible for flu pandemics in humans, most notably the 1918 pandemic, which was more horrifying than I can possibly imagine. Although estimates vary widely, the USA Centres for Disease Control estimates that 500 million were infected and 50 million died. There have been other human pandemics since, but none has come close to 1918.

Although Influenza A can infect many types of animal, this doesn’t mean that every influenza A virus can infect every one of those animals. It has many subtypes, each of them subtly different in the animals they infect and how sick they make their host. The subtypes of Influenza A are categorised by proteins which occur on the surface of the virus. There are two main kinds of protein, usually known as H (short for haemagglutinin) and N (short for neuramidase) and every Influenza A virus has both. I learned from one of the talks at the symposium that the H protein is responsible for the virus attaching to and entering cells, while the N protein is involved in the release of new viruses from infected cells. Their functions are more complicated than that though, and scientists continue to study them.

There are 18 known variations of the H protein and 11 of the N. These variations affect the animals which are infected and how sick they get. The severe bird flu which has been killing birds around the world has the 5th type of H protein and the 1st type of N protein, which means it’s known as H5N1. The 1918 pandemic was caused by an H1N1 flu virus, although not every H1N1 virus is so deadly.

The virus detected in Otago is H7N6, which means it’s different from the bird flu spreading around the world. Why, then, has it prompted such concern?

As well as the variation in H and N proteins, flu in birds is also classified by severity. Many forms cause only mild disease, and are classified as low pathogenicity. Forms which cause severe disease are known as highly pathogenic. New Zealand has long had forms which cause mild disease in our bird populations, but not severe forms. Otago’s cases are of the severe form, the first time any of these has been reported in New Zealand.

How did the severe form get into chickens on an Otago farm? So far, experts are suggesting that it may have resulted from forms of the virus already present here mutating. This has been reported in Australia over the past few months, also with H7 forms of the virus. Fortunately, although H7 and N6 viruses can infect humans, they don’t do so often.

Why is there such a dizzying diversity of influenza A, and why does it sometimes mutate from mild to severe forms? Part of the reason is because influenza A has a particularly high rate of mutation in comparison with other viruses. But it isn’t mutation alone which makes influenza A change so much. The other reason is a process called reassortment.

We’re used to the idea that children have genes which are a mix of genes from both parents. But the same thing can happen with viruses like influenza A. When two different subtypes of influenza A infect the same host, they can swap fragments of their genetic code, resulting in new subtypes of the virus.

This ability to change is one reason why scientists are watching the H5N1 outbreak overseas with such concern. So far, it has been dangerous to humans who have come into contact with infected animals, but human-to human spread isn’t reported. However, there are some ominous signs.

Over the last year, H5N1 flu has moved into US dairy cattle herds. This is more than simply cows coming into contact with infected wild birds – it’s spreading from cow to cow. It isn’t as deadly to cows as it has been to chickens and many kinds of wild birds. But other animals have caught the virus from infected cattle, and some, such as cats, have died. So far, farm workers who have caught this flu have only had a mild illness. While it’s good they have recovered, the cases are still important, because they are the first known cases of H5N1 spreading to humans from another mammal.

Another worry is that the virus is concentrated in the milk of infected cows. On the whole, that’s not a risk to us, because the virus is killed by pasteurisation. However, it is able to survive in raw milk for some time. It’s a troubling finding at a time when the incoming US president’s nominee to head the Department of Health has promoted drinking raw milk.

A third ominous sign has come from Canada, where a case of H5N1 flu was reported in a teenager. The case wasn’t linked to the outbreak in dairy cows and the teenager hadn’t had any known contact with animals which carry the virus. So where it came from is still a mystery. More ominously, genetic analysis of the virus from this case showed mutations which may allow it to infect humans more easily.

The outbreak of bird flu in Otago is awful for those affected. 80,000 chickens have been killed to stop the disease spreading. As I write this article, the virus has been detected at only one farm, and nearby farms have been found clear. So far, the people of New Zealand, as well as our chickens, cattle and wild animals, have been lucky. But flu is a constantly changing virus. It jumps between species, travels around the world on migratory birds, and tears through poultry flocks kept in crowded conditions. It’s only a matter of time before it brings us new and unwanted surprises.

Thanks Melanie - I actually found that Venn diagram about one health a bit of a revelation. Of course, I understood that human, environmental, and animal health are related, but for decades now we've been led to believe that simply the "right combination of technology and progress" will allow us to isolate ourselves from the rest of that diagram - it's just a matter of time and effort. But, seeing the deceptive simplicity of the interactions, it is clear how naive and insane it is to think any amount of progress will ever actually detach us from our fundamental reality, because these interactions cause the environmental and animal interactions to simply evolve right alongside us.

Great graphics, Melanie!

A friend of mine just moved from Public Health Director of our county to Deputy Director of One Health for the state, a loss for the county but a win for him and for the state. Washington is keeping in touch directly and discretely on H5N1 by text message with our farm workers, who are majority migrant workers of varied status and hard to reach through other channels.

Also, on the plane, I thought of you when we were given a biosecurity form. Brenda has a wetsuit for the race and I a mask and snorkel, all washed in clean water before we left. I declared them and got a big thank you from the biosecurity officer at the airport.