I planned to continue my theme of plants and ancient Rome for today’s article, but I’ve been totally sidetracked by the City Nature Challenge, the event where people around the world try to make as many observations of nature as they can in four days. So, instead I’m going to share a few joys from my participation in this event.

On Friday, I put on a high-vis vest and spent three hours standing beside one of the park benches in Khandallah Park. I was running a session to help people who wanted assistance with iNaturalist, or who wanted to learn more about plants and animals, or just wanted to hang out with other people who were interested in nature. I didn’t actually put many observations into iNaturalist, because I was kept busy chatting with people and showing them some of the forms of life that they might not have noticed on their walk through the park.

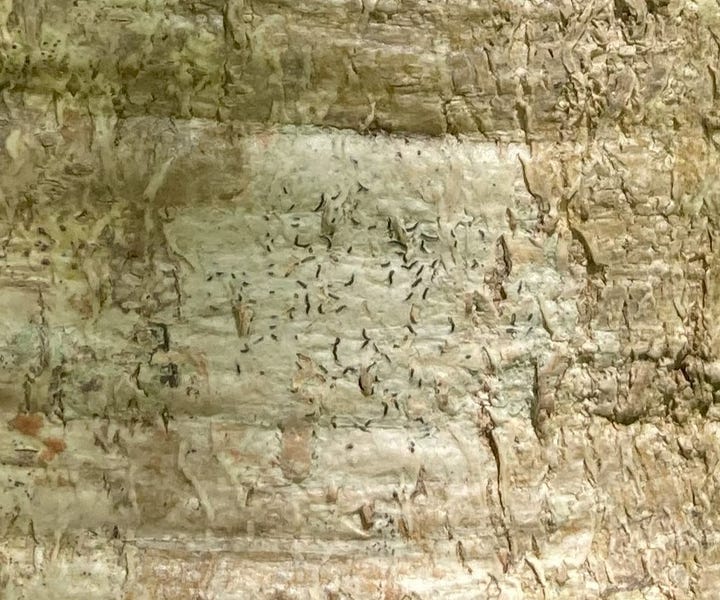

Most of the time, when I’m in the forest I’m not wearing the glasses I now require for close vision. However, since I needed to look at my phone for iNaturalist, I was wearing glasses, and it made me shift my perspective. At first glance, a tree is just a tree – trunk, branches, twigs and leaves, with roots under the ground. But look more closely, and the tree’s companions become visible. Insects leave holes where they’ve fed on the leaves, microbes grow into the plant’s tissues, and the tree’s bark is encrusted with one of the world’s most remarkable life forms.

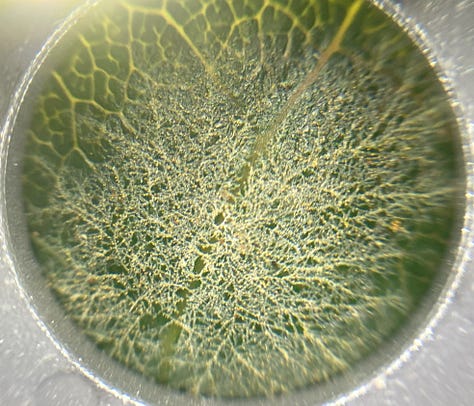

Adding to my enthusiasm for the close-up world, I had found my phone’s microscope attachment a few weeks ago, and had put in new batteries, so I could take photographs. It means I could put them onto iNaturalist for the City Nature Challenge, but it also means I can share them with you.

When an insect feeds on a plant, it leaves distinctive traces. Some chew the edge of a leaf, turning a smooth leaf margin ragged. Others chew meticulously neat holes, or graze haphazardly, until some leaves are more hole than leaf. Some, too, scrape away only parts of the leaf surface, with the remaining tissue appearing translucent, as if the leaf has windows. Then, there are those with piercing mouthparts, like tiny needles, which they use to suck the plant’s sap. Some even tunnel inside leaves, marking them with characteristic trails.

When I look at this kind of damage, I don’t usually know exactly what has caused it. Chewing damage to edges or holes in the middle of leaves are often made by beetles or caterpillars, but this doesn’t really narrow it down. New Zealand has more than 5000 native beetles and more than 1800 native butterflies and moths. We also have around 800 species belonging to the sap-sucking group. There’s no guarantee that damage on native plants is caused by native insects either. It could have been caused by a species which we have brought to New Zealand, either intentionally or unintentionally.

Sometimes, the plants give me clues as to what has been eating them. A few of the leaves of my rocket plants have the distinctive trails left by insects tunnelling inside the leaves. Rocket belongs to the same botanical family as cabbage and other brassicas. And there’s a kind of fly whose juvenile stages tunnel inside the leaves of plants in that family. Although I haven’t found a definite record of this fly on rocket, it’s a likely culprit.

Although they can’t move, plants are not defenceless. The damage caused by insects triggers chemical responses within the leaves, part of the plant’s immune system. Yes, plants have an immune system, just as we do. It’s probably worth a whole article at some stage, because it’s fascinating, at least in my view. The ways that plants respond often leave a mark, such as discolouring the leaf with spots or blotches. Close up, these marks have their own kind of beauty, coloured in greens, yellows, reds and browns.

There are also microbes which are parasites on living plants, known as pathogens. Although they are taking their nutrition from the plant, apparently without offering anything in exchange, they don’t necessarily harm their host plant. At Cashmere Park where I’m helping with the forest restoration, there are a number of native tree fuchsias planted last winter, when they were around a foot tall. A close inspection of the leaves reveals that most plants are infected with a kind of fungus known as a rust. However, it doesn’t seem to have had much effect on their growth. Some of the plants are nearly as tall as me now.

Another parasite which doesn’t appear to do much harm is a kind of algae which causes leaf spots on a number of native trees, but especially māhoe. At first the spots are whitish, but they eventually become yellowish-brown, and they are often very conspicuous. A quick check of iNaturalist shows that during the two days of the City Nature Challenge so far, there are 15 separate records of the māhoe leaf spot from around New Zealand, including mine.

This doesn’t mean that some pathogens aren’t harmful. I’ve previously written about the destruction caused by myrtle rust, which is endangering a number of native trees and shrubs in New Zealand, and many more in Australia. However, when plants and pathogens have evolved together, they generally reach a kind of détente.

An altogether more cosy relationship is the one which certain fungi have formed with either algae or a kind of bacteria. These relationships are so close, that the resulting life form is given its own scientific name, separate from either partner. The fungus provides the home – anchorage to a stable surface, a structure for the algae or bacteria to live in, protection from the elements – and absorbs water and minerals from the environment. The algae or bacteria create food from sunlight, carbon dioxide and water, which feeds the fungus. They are sometimes described as “fungi which have discovered agriculture”, a quote usually attributed to Canadian lichen expert Trevor Goward.

Lichens are incredibly adaptable, and can be found from the tropics to polar regions, from sea level to the highest mountains. They are found in places no plant can survive – the highest elevation where plants grow is around 6000 metres, while lichens can be found at 7400 metres. But there’s no need to go anywhere exotic to see lichens. You might spot one on a path, on a tree branch, on a brick wall or a steel roof. Once your eyes get used to spotting them, they are everywhere. Friday’s session at Khandallah Park reminded me to pay more attention to them, and I'm so glad I did. I'd forgotten just how beautiful and extraordinary they are.

Lichens take one of three different growth forms. The first group press themselves so close to the surface they are growing on that there’s barely a bump, just a change in colour. The second group form flattened lobes which are attached in places to the surface they are growing on, but can be lifted off with some care. These can be tiny, such as one I came across on the asphalt of a carpark while I was shopping today. But in ancient, damp forests, some species extravagantly festoon the branches of trees, like the flounces of a flamenco skirt. The third group form complex, three-dimensional structures. While never large, these can carpet the ground or hang from the trees.

My session at Khandallah Park reminded me how much I like lichens, when I take the time to look at them. So, when I took my dog Donna to Cashmere Park for a run and to help me weed around the new plants, I looked out for lichens. I was rewarded with some treasures which I had been walking past for years. They aren’t anything unusual, but they are exquisite. The sight of them filled me with joy. They reminded me that in nature, whether in the forest, in a patch of roadside weeds, in a lovingly-tended garden or even in a few pots on a deck, there is always more to see if you take a closer look.

Lichens are amazing. I'm always fascinated by their unique shapes, strange beauty, and the colours! I've even seen some of them glow in the South Indian Shola Forest!