Confidence, complacency and convenience

What’s going wrong with vaccination in the United States, the United Kingdom and Israel? (7 minute read)

Listening to the international news right now is an odd experience. While New Zealand is once again locked down, many countries overseas are finally opening up. It’s the opposite of how things have been since June last year. New Zealanders have enjoyed concerts, sporting events and other massed gatherings, while the rest of the world has limped along with restrictions somewhere between our levels 2 and 3.

Superficially, our current situation looks like a failure. As the graph below shows, we are behind other wealthy countries when it comes to vaccination rates, even if we’ve still managed to jump the queue in comparison to less wealthy countries. It is frightening to have Delta spreading in the community with not much more than 25% of the population fully vaccinated. There’s no doubt in my mind that we need to get more people vaccinated as soon as possible.

But a closer look at what is happening in some of those well-vaccinated countries shows a worrying picture. Daily Covid-19 deaths have been rising in countries with comparatively high vaccination rates, such as Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States and Israel. I was expecting the number of cases to rise, given the increased infectivity and the decreased ability of vaccines to prevent transmission for the Delta variant. But rising deaths? Wasn’t that what vaccines were supposed to prevent?

The problem, though, is not with the vaccine. The evidence is still showing that the vaccines themselves are doing their job, as promised. As an example, a few days ago, a study came out from the Los Angeles Department of Public Health, reporting that unvaccinated people are 29 times more likely than the vaccinated to end up in hospital with Covid-19. That study was based on data from May-July 2021, and it covered the period when the Delta variant went from uncommon to dominant. People who have been vaccinated are catching Covid-19, and some are even being hospitalised and dying, but, even with the Delta variant, the numbers are small in comparison with the numbers for the unvaccinated.

The main problem is shown in the first graph above – the percentages of people who are fully vaccinated, even in countries with “high” vaccination rates, aren’t actually all that high. Israel, which managed to jump the queue after making a controversial deal with Pfizer, has vaccinated just over 60% of its population, as has Britain. The USA has only vaccinated just over 50%. Spain is doing better, but still hasn’t quite reached 70%.

Those numbers are worrying. As I mentioned in one of my articles about vaccination last year, New Zealand is generally behind other countries in terms of childhood vaccination rates. The data for the influenza vaccination are better – we are near the top, just slightly higher than the USA and UK, but our rate is still low, at just over 70%. If we can’t do substantially better than that for Covid-19, we will either need to keep our border closed, or accept hundreds of people dying from the virus.

But it’s not just the percentage who have been vaccinated in the USA, the UK and Israel that is worrying. The vaccination rates in these countries have slowed considerably. Israel had vaccinated 50% of the population back in March, but did not pass 60% until the end of July. The vaccination rate hasn’t slowed quite as much in the USA and the UK, but there’s still a definite decrease. It made me wonder whether they’ve vaccinated everyone who wanted it, and are now left with those who don’t want to be vaccinated.

However, when I took a closer look, I found that wasn’t true. The vaccines used in those countries haven’t yet been approved for children under 12 (under 16 in the UK). This means that just under 20% of the population in the USA and UK, and just under 30% of the population of Israel cannot yet be vaccinated. But it still leaves a significant number of unvaccinated adults and teens. What’s going on?

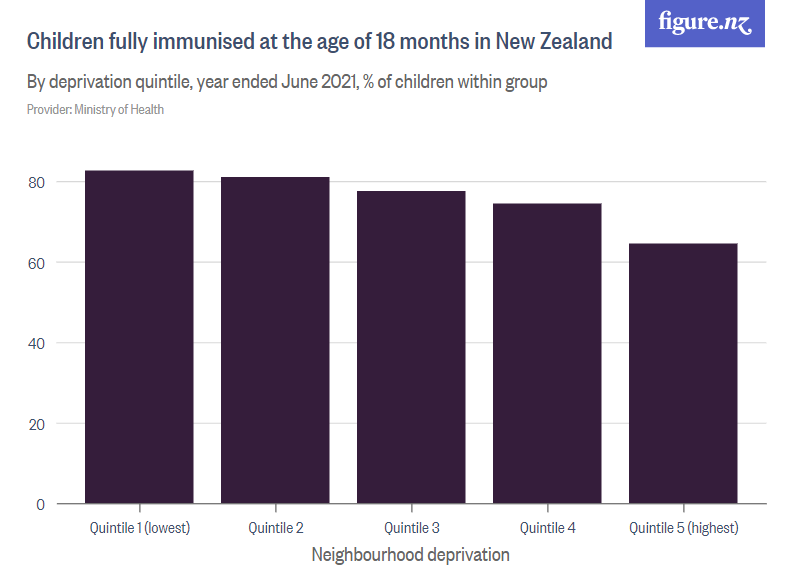

For the USA, there’s one obvious problem – political polarisation. There’s a sharp, and growing, difference in vaccination rates between Republican and Democrat voters. But it’s much more complex than that. There are three other factors linked to vaccination rate in the USA – age, income and race. Similar factors, in particular age, are seen in the UK and Israel. And we already know that economic deprivation is linked to lowered vaccination rates in New Zealand.

But age, income, race and political affiliation are not reasons for people to avoid vaccination, they are just factors that are linked in the data. To understand the reasons, you need to take a closer look. Why are some groups less likely to be vaccinated, and is there anything that can change that?

One of the most helpful ways to understand vaccine hesitancy and opposition is a model used by the World Health Organisation. Although they describe vaccine hesitancy as complex and context-specific, they summarise the reasons that people delay or refuse vaccination as related to one or more of three factors – confidence, complacency and convenience, or the “3Cs”. These reasons immediately make intuitive sense. For example, one obvious reason that younger people may be less likely to get vaccinated against Covid-19 is that they consider their own risk from the disease to be minimal, in other words, complacency. “Convenience” – perhaps not quite the right word – is one reason those on lower incomes are less likely to be vaccinated. For me, there’s very little effort or expense in getting into my car and driving to my closest vaccination centre, as I did earlier this week when I got my first Covid-19 shot. But someone on a lower income may have a harder time. They may not have a car, or may only have a limited amount to spend on fuel. They may have to catch a bus and spend money, or walk and spend more time.

“Confidence” is perhaps the most complex of the factors. It can be confidence in the vaccine itself, but it is much more than that. It relates to confidence in the people who give vaccines, confidence in those who promote vaccines, confidence in those who regulate vaccines and confidence in those who manufacture vaccines. A lack of confidence in any one of these can undermine confidence in vaccination. It can also drive people to seek and believe information from unreliable social media sources.

The advantage of the “confidence, complacency, convenience” model is that it makes vaccine hesitancy, and outright opposition to vaccines, more understandable. An example is the vaccine boycott that happened in northern Nigeria in 2003, which nearly derailed the global programme to eradicate polio. If you’re an advocate of vaccines, as I am, it’s hard to have sympathy for religious and political leaders claiming that the polio vaccine is part of a Western plot to sterilise Muslims. However, if you look at the vaccine boycott through the “confidence, complacency, convenience” lens, it makes a lot more sense. As described in this excellent review, the people of northern Nigeria had good reasons not to trust vaccination. Here’s just one example – in 2001 the drug company Pfizer (yes, that Pfizer) was reported to have conducted an antibiotic trial on children in northern Nigeria without obtaining the required ethical approval.

But the point of framing vaccine hesitancy in terms of “confidence, complacency and convenience” isn’t to gain sympathy for those opposing vaccines. The point is, if we want to bring an end to the pandemic, and safely open New Zealand’s borders, we need to get as many people vaccinated as possible. And to do that, we need to have a sensible conversation about how to convince people to get vaccinated.

When I look at some of what is happening overseas – vaccine passports, making the unvaccinated pay, or making vaccination mandatory for certain jobs – I find myself asking questions. Are these approaches based on a careful consideration of what is stopping people from getting vaccinated? Are these approaches protecting public health, or do they just “feel right” to frustrated people who’ve been vaccinated? Do they risk creating a backlash? Those are the questions I will answer next week.

You may have noticed this week that I have changed the font for The Turnstone. It think the new font may be easier to read. What do you think? Let me know if you love it or hate it.

We need the vaccine for all school aged children... before we can really have safe institutions

Yep, I like it too Mel, very easy on the eye :-)