Generating controversy

How to diminish the deluge of disinformation (10 minute read)

The world I know is filtered through a particular lens – that of the English language. Although I’ve learned to say hello and thank you in a dozen or so languages, I’ve never learned to speak another properly. The closest I’ve come is the very basic conversations I was able to have in Mauritius, and being able to make a tolerable effort at introducing myself in Māori.

I’m a bit embarrassed to admit this, to be honest. I feel as if I should have made more effort. Monolingual people make up less than half of the world’s population, so speaking another language isn’t some rare, mysterious talent. When I have some spare time, maybe…

As a substitute for speaking and understanding another language, I enjoy hearing the perspectives of those who do. Perhaps ironically, one of my favourite sources for this is the BBC. Although it might seem to be a contributor to the predominance of English, the BBC has services in over forty languages. Every week, some of the people working for these local language services switch to English and contribute to a programme called The Fifth Floor. It’s one of my favourite radio shows and I highly recommend it.

A few days ago there was a collision this show and the topic I’m currently writing about. Journalists from Russia, Latin America and Nigeria spoke about disinformation. I listened to it during my lunch break and it was fascinating, if a little disturbing. These journalists spoke about a few topics I was aware of but hadn’t explored in detail. So, I decided to look at a couple of the topics they discussed.

Here's a link to their conversation if you would like to listen to it yourself.

The Fifth Floor - The disinformation wars - BBC Sounds

Farming trouble

One of the things they spoke about was the motivation behind some disinformation. It’s understandable that people wanting to promote their side in a conflict might use false footage to claim success. A well-documented example is claiming that footage from a video game called Arma-3 actually came from Ukraine or Gaza.

Here’s a video analysing disinformation from Gaza coming from both sides.

'Arma 3': This is video game footage, not the war in Gaza - Truth or Fake (france24.com) (6 minute video)

Here’s an article about the use of the same video game in the Ukraine war.

War-themed video game fuels wave of misinformation (france24.com) (4 minute read)

But why would someone take footage of a bridge being blown up in Crimea and pretend it was the Baltimore bridge collapse? The answer, as I learned from The Fifth Floor, is something known as engagement farming. So far, this seems to be a term which exists mostly on social media, but it’s starting to be used by disinformation researchers such as Caroline Orr. Basically, it means posting material on social media which is intentionally provocative in order to get more attention. It’s similar to the term clickbait, which is using misleading headlines to get people to visit a website.

It isn’t just about attention. On the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, users who get a lot of attention get a portion of the advertising revenue generated by their posts.

A subset of engagement farming is what Caroline Orr calls rage farming – engagement farming aimed at making people angry. I’ve linked to an article below where she talks about a particular social media post which got a lot of attention because it made people angry. One group of people was angry because they agreed with the sentiment of the post, while another was angry that their position was being grossly misrepresented. As far as social media algorithms are concerned, it doesn’t matter why you are angry. If you like, comment on or share the post – you’re making someone money.

For more on the role of disinformation in social media’s business model, here are a couple of articles.

The Anatomy of a Viral Tweet: Rage Farming Edition (substack.com) (10 minute read)

Disinformation is part and parcel of social media’s business model, new research shows (theconversation.com) (4 minute read)

Doing the laundry

Another disturbing term I learned from The Fifth Floor was disinformation laundering. It’s like money laundering, only with lies. You’ve probably heard variations on the saying If you repeat a lie often enough, it becomes the truth. Perhaps you’ve heard this attributed to Joseph Goebbels, but that’s actually untrue – ironically proving the quote.

Hitler, however, did say that propaganda:

should be persistently repeated until the very last individual has come to grasp the idea

Here’s an example. Before I start, I’m going to do some pre-bunking – there are some false claims that Volodymyr Zelenskyy has recently purchased luxury yachts. He hasn’t. In fact, the yachts in question are still for sale.

So how did such a claim end up discussed in US Congress debates about aid to Ukraine?

This case is an example of disinformation laundering. According to the BBC, the claim was first made on an obscure YouTube channel. It was then picked up by a website with the name DC Weekly. A name like that might imply it had something to do with the District of Columbia in the USA, but it originated with an American who now lives in Russia and mostly writes about Ukraine. Although I haven’t been able to find that website, it’s linked to other websites which might appear to be American but have suspicious content such as the Boston Times. It sounds as if it should be a newspaper from the largest city in Massachusetts, and it was, until 1943. However, recently, it’s been an online-only publication, sharing anti-Ukraine disinformation among its more regular stories.

Russian embassy shares disinformation on alleged atrocities by foreign mercenaries in Ukraine (france24.com) (4 minute read)

DC Weekly and the Boston Times are not the only news websites which sound American but originate in Russia – that’s something of a research rabbit hole I went down trying to understand the issue. There’s also the slightly different tactic of creating websites which look like respected sites such as The Guardian.

Doppelganger - Media clones serving Russian propaganda - EU DisinfoLab (4 minute summary, full report 26 pages)

The point about these sites is that they are superficially plausible. The articles are spread on social media and people fall for them. In the case of the claim that Zelenskyy had purchased luxury yachts, a couple of Republican senators picked up the news and began talking about it. At that point, Russian disinformation about Ukraine had become part of mainstream US discussion.

Here’s the BBC article about the false yacht story.

How pro-Russian 'yacht' propaganda influenced US debate over Ukraine aid (bbc.com) (8 minute read)

Real or fake

People have been faking photos for as long as there have been cameras. More than 100 years ago, many people were fooled by a photograph of a young girl with dancing fairies. More recently, digital cameras and photo manipulation software made faking photos much easier, but it still required some skill. Then generative artificial intelligence, or AI arrived, and the internet was flooded with fake images created simply by entering a few prompt words into a website.

It's easy to see the risks. On the one hand, there’s the risk that people will believe that images like these AI-generated Trump arrest photos are real. On the other hand, it can make us doubt everything we see. And then there are malicious uses, such as creating fake explicit images of someone, as happened to singer Taylor Swift earlier this year. I’m not going to get further into the risks of AI here, but it’s a topic I will come back to.

Some of the AI images aren’t good fakes (I’ve included a monstrous example below). AI can have trouble with counting appendages such as fingers and even sometimes arms and legs, although it is getting better. The types of AI which create images are different from the types which read text, and so if there is text in an AI image, it’s often nonsense. AI also struggles with things like the texture of human skin. Still, sometimes it’s hard to tell, and AI is improving all the time.

4 tips for spotting deepfakes and other AI-generated images : Life Kit : NPR (7 minute read)

4 tips for detecting AI-generated images • FRANCE 24 English (youtube.com) (6 minute video)

If you want to go into more depth, digital investigator Benjamin Strick has some excellent videos, such as this one here.

AI-Generated Fakes: How to spot them, how they're made and how they have been used to mislead (youtube.com) (25 minute video)

I tried out a couple of tests, and I couldn’t reliably tell just from looking at the images. That’s where the skills in the next section becomes useful.

If you want to try yourself, here are two good tests.

Real or AI Quiz: Can You Tell the Difference? » Britannica (britannicaeducation.com)

Quiz: Artificial intelligence or real? - BBC Bitesize

How to be suspicious

Not all AI images are as catastrophically bad as the nightmare I’ve included above. Figuring out whether an image is real can take some investigation. But there’s an easy way to trace images on the internet – reverse image search. By searching for an image, you can see where it came from, and can make a better judgement on whether it’s real. You can apply the other skills you have, such as lateral reading, to see whether it’s a credible image.

Reverse image searching is one of the suggestions from the journalists interviewed on The Fifth Floor. On their recommendation, I’ve learned to do it, and it’s incredibly simple. For those who’ve never done it and might feel too technologically challenged, you really aren’t. There are various ways to do it, but I’m going to show you the simplest method which works with either the Edge or Chrome browser:

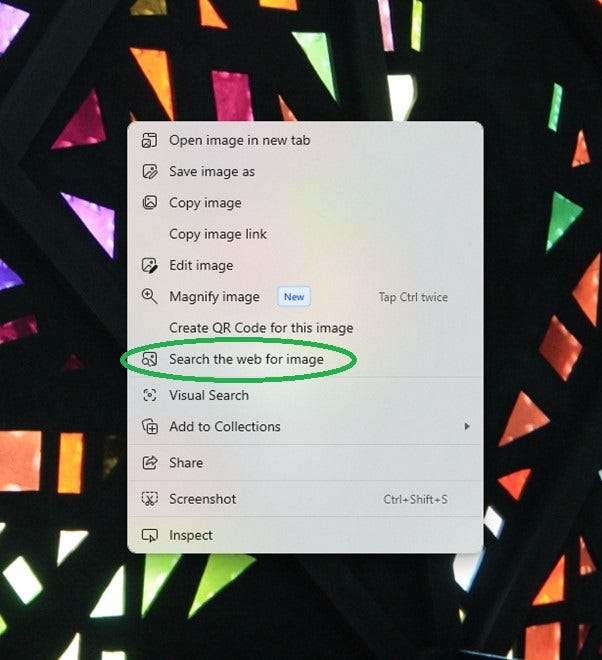

Right click on the image you want to search for

You will then get a menu of options. In the two images – on the left hand side is what you’ll see if you are using Edge, on the right, what you will see in Chrome

Select the option which says either: search the web for image or search for image with Google

And that’s it.

If you want to try, here’s an image of stained glass, which I published a few weeks ago. However, if you are reading this in an email, you’ll need to left click once on the photo first, which will take you to your browser. Then you can do the search. The first result you see should have the exact image I published, and will be linked to my Substack. There will be other photos of the same stained glass window. From that, you should be able to work out where I took the photo (if you can’t get it to work, let me know).

Once you get good at this, it’s incredibly useful. It only takes a few seconds, and it could save you from contributing to the deluge of disinformation on social media.

For an example of what a good reverse image search can do, here’s an article from India Today, which does a good analysis of commonly-shared photos at the start of the war in Ukraine. These are largely from before AI images became commonplace, but the skills are the same.

Fact Check: Old, unrelated images passed off as recent photos from Ukraine - India Today (4 minute read)

If you want to know more about investigating images, Benjamin Strick has a couple of excellent videos explaining the process in more detail. The exact method for searching has changed slightly, but he covers the investigative aspects as well.

Checking online images, Benjamin Strick

The final suggestion from The Fifth Floor journalists was to remind people to take a few seconds to think before you share something. This suggestion prompted me to think about the role of intuition, so I’ll be writing about that next week.

Thanks, Melanie, for this great series.

"People have been faking photos for as long as there have been cameras." In warfare, sometimes actual photos and actual things may be fake. Among the many examples of fakery an example is the fake tanks used to trick the German military about where the (ultimately) Normandy invasion would take place.

Thanks very much for the informative article. I guess we should be wary of not only the actual words used in a particular language but also the tendency to morph meanings to fit one's purpose. Some serve a noble purpose - the subtle name shift used by the environmental movement that renamed "jungles" as "rainforests"; preferred energy sources as "green" (green means 'go', green is 'good'). Other changes could be more nefarious -- changing "riots" (property destruction, arson, etc.) to "protests" makes riots more acceptable. It seems beyond the money, propaganda can hold important agenda. Depending on your point of view, it can be used for good or evil, quoting Dylan "And you never ask questions when God's on your side." (Bob Dylan, With God on Our Side, circa 1963).