The sportsfield at my primary school in Auckland wasn’t my favourite place. Running races were humiliating, because I was the slowest runner in my year. I can still remember the only time I wasn’t last, when one of the other girls got a prickle in her foot and stopped to pull it out. But the team sports were worse. I could barely throw or catch a ball, so I would always let my team down.

The only time I remember enjoying team sports was when there was a tournament with other schools and I was placed in a team with students from the year below me. I don’t know whether it was just a case of balancing numbers, or whether the teachers decided to try and make it easier for me. It was a good call, because my skills turned out to be about average among the students I was teamed with. Sport made a lot more sense when I was more equally matched with my team and competitors.

Beyond the sportsfield though, there was another field, and it was my favourite place in the school. We called it the bottom field, because beyond the sportsfield there was a steeply sloping embankment and then another flat field a couple of metres lower than the sportsfield. We never used the bottom field for any kind of sports, except the occasional cross-country run, because about half of it was covered by large trees. Instead, it was a place for imagination.

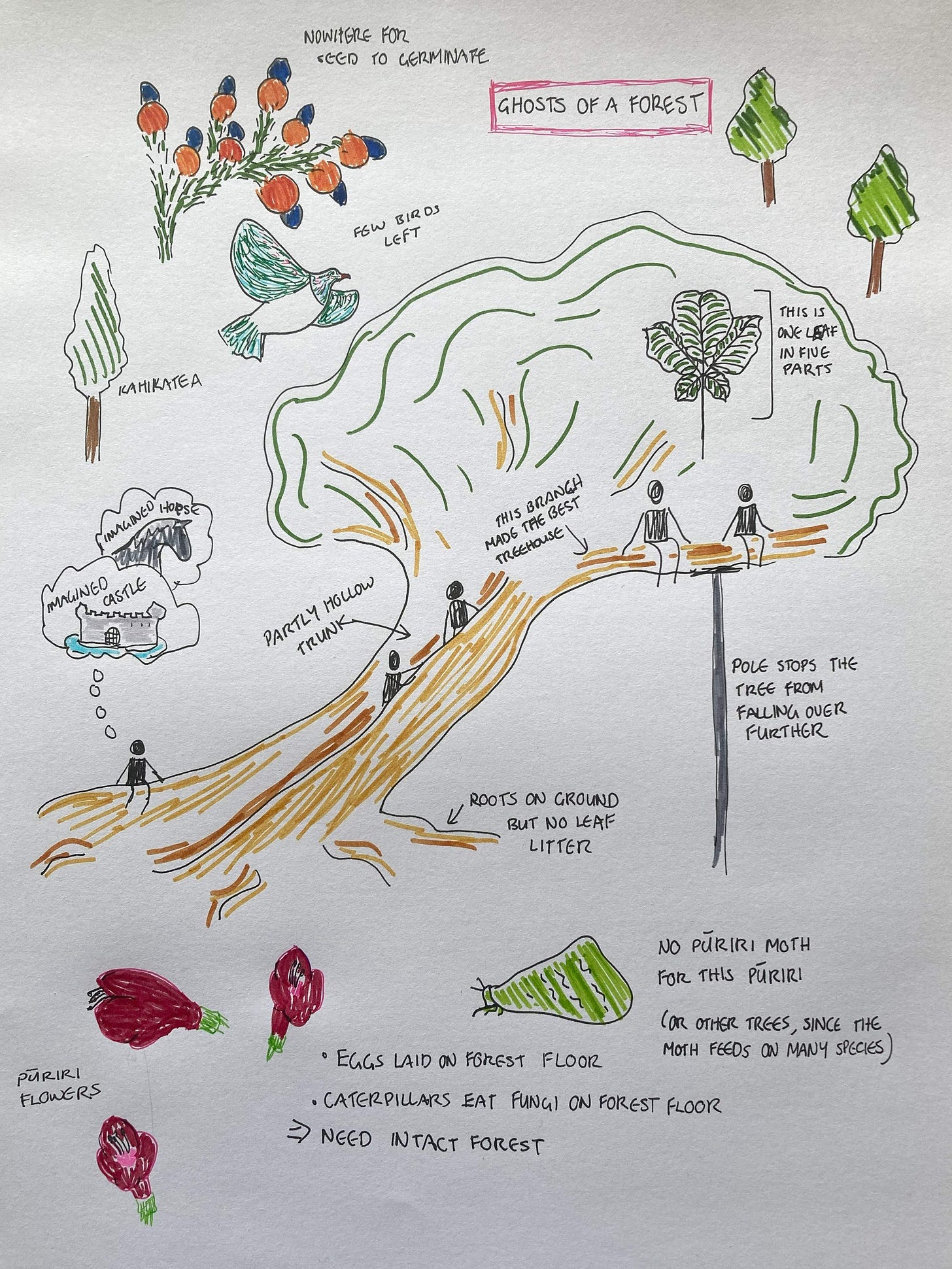

I can remember various games my friend and I used to play on the bottom field. We collected grass clippings to construct walls for imaginary houses or castles, or fences and jumps for our imaginary horses. We used pieces of bark as plates and gathered flowers for pretend meals or mashed them up into magic potions. We built elaborate worlds there, and the trees always formed the landscape for those worlds. I can still picture those trees today, in detail. I remember the peeling strips of tōtara bark, the slightly resinous taste of kahikatea fruit, the twisted trunk of an old pūriri.

We used to climb the pūriri, scrambling along the sloping trunk, which was hollowed out with age and rot, almost like a canoe. In places, the bark was worn smooth by the hands and feet of hundreds of children over the years. Elsewhere, the bark was soft, almost velvety. It’s not much to look at, but it’s beautiful bark to touch.

Among New Zealand trees, the pūriri is something of an oddity. The flowers are relatively large and they are a dark pink colour instead of white or cream. It has an exotic appearance in the forest, with large, glossy leaves made up of five individual leaflets radiating from a single point and its branches which are often laden with epiphytes – plants which perch on other plants but don’t derive any nutrients from them. It’s the kind of plant you might imagine growing in the jungle, and indeed it almost could, because most of its relatives are tropical.

Living in Wellington, I miss seeing pūriri trees. Although there are a few around, they are all relatively small, as they have been planted here. Pūriri occurs naturally only as far south as Taranaki and the northern Hawkes Bay, and is common only in the northern third of the North Island. In these northern regions it’s not unusual to see gnarled old trees in suburbs, on farms or in forest remnants – rejects from foresters who cut down all the vigorous, straight specimens.

When I was a child, those trees made a wonderful playground, but I view them differently now. I can’t help picturing how they once grew. I picture the dense forest canopy, the tree branches dripping with moss and lichen, the undergrowth thick with shrubs and ferns. I imagine the birds singing in the branches, scrambling up and down the tree trunks and fossicking on the forest floor, as they did without fear before humans came and brought predators the birds weren’t adapted to. I remember the thin layer of fine leaf litter created by the kahikatea trees and compare it with the deep carpet in a healthy forest. That dense canopy, thick undergrowth and deep carpet filtered and regulated the rain that fell, so that the streams ran pure and clear, without too many big floods, and the harbour was lined with sandy beaches and shellfish beds. Today, the area downstream from my old school is highly flood-prone and the harbour is lined with stinking mud, which was washed from the land when the forests protecting the soil were stripped away.

Those trees were the ghosts of that long-gone forest. There was nothing but grass or bare ground beneath them, and it’s unlikely there will be a new generation of pūriri, kahikatea and tōtara to succeed them. In some places, such as Huntleigh Park, near where I live now in Wellington, there are ancient survivors in reserves where the weeds and predators are under control. But in the suburb of Auckland where I grew up, the old trees are in reserves too small and fragmented to sustain a functioning forest. There’s one special reserve nearby, Smith’s Bush, which I’ll tell you about next week. Even that, though, is more of a cautionary tale.

I know that we have to live somewhere, and that children have to go to school somewhere, but those ghostly trees remind me that we have to find a better balance with nature. Our fresh water, our coasts, our biodiversity and, of course, our climate all need us to have more land in healthy, native forest. So, my memories of those trees trouble me, but they still bring me joy. The bottom field was where I first appreciated native trees. It was where I first observed them closely, where I learned not only what they looked like, but what they felt like, smelled like and tasted like. And it's where native trees first found their way into my imagination and became a part of my storytelling. Those trees are still with me today.

Come up the Kāpiti Coast to Ngā Manu Nature Reserve. There you’ll find puriri, always in flower or currently dripping with fruit, laden with tui and kereru. They’re hard to grow from seed though.

Trees or anything in nature always sparks the creative mind in my experience. Great memory!