Not there yet

How have countries with previously high vaccine hesitancy managed their vaccine programmes? (8 minute read)

Welcome to The Turnstone. Here, I share my perspective on science, society and the environment. I send my articles out every Sunday - if you’d like them emailed to you directly, you can sign up to my mailing list.

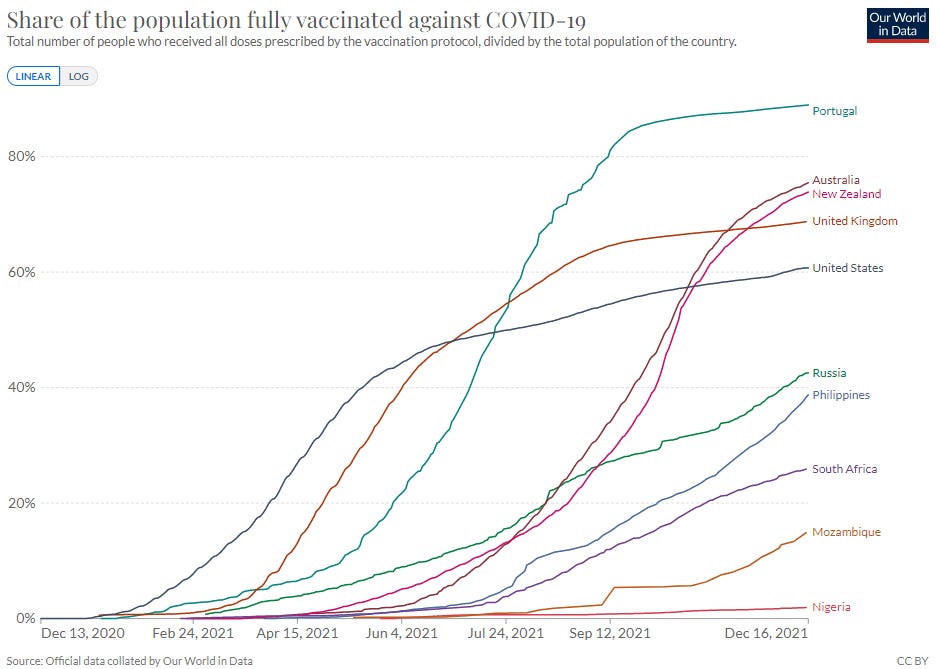

It may not seem like it as we adjust to the new system of Covid-19 restrictions, but New Zealand is heading into Christmas and the holiday season in an enviable position. Although our vaccination programme started slowly, we are now ahead of countries which started much earlier, such as Israel, the United States and Britain. We now have 90% of the eligible population fully vaccinated against Covid-19. Medsafe has just approved the Pfizer/ BioNTech vaccine for children aged from 5-11 years. Booster doses are available for those who had their second shot more than 6 months ago.

A few months ago, it was far from certain that we’d reach this point. A survey done in March 2021 showed that only 56% of New Zealanders over 18 said they were very likely to get vaccinated, with another 15% considering themselves “somewhat likely”. It has been an outstanding effort to get to where we are now.

But I can’t help thinking about countries that aren’t so well off. Within our own borders, we can feel pleased about vaccination, but the public health measures and vaccination programmes in other countries matter as well. The more unvaccinated people and Covid-19 cases there are, the greater the chances that new variants, like Omicron, will emerge. Even if our own vaccination programme is now going relatively well, we won’t be safe until the whole world brings Covid-19 under control.

I particularly wonder about countries that already faced considerable vaccine hesitancy. If many people in the population didn’t trust vaccination before Covid-19 arrived, how have they fared in the pandemic?

One country where vaccine confidence has plummeted in the last 5 years is the Philippines. The reason is that there has been a major controversy over Dengvaxia, a vaccine against dengue fever. Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne disease which is common in the Philippines, and can be severe, but the vaccine also has rare side effects which are potentially dangerous. Fueled by misinformation, controversy over the vaccine became politicised, with the Public Attorney’s Office in the Philippines blaming Dengvaxia for dozens of deaths. Although a panel of experts from the Philippine General Hospital concluded the vaccine wasn’t to blame, the damage was done.

There’s no doubt that Dengvaxia is influencing the people’s opinions on Covid-19 vaccination. A September 2020 survey showed that the numbers of people willing to be vaccinated with Dengvaxia and Covid-19 vaccines were similar. Less than 25% of the people surveyed were certain they’d get vaccinated with either vaccine.

Bearing that figure in mind, it appears that the Philippines has done well. They have now fully vaccinated more than 43 million people, around 40% of the population. That means they are making progress with the substantial percentage of the population, around 35%, who were uncertain about being vaccinated in September 2020.

To get an idea how the vaccination programme is being received on the ground, I speak to a local contact there, Octrine Micu. I’ve got to know Micu online over the last year through a plant identification group, where she’s an excellent contributor. She tells me that she thinks most people are in favour of Covid-19 vaccination, even though concern about side effects and misinformation do persist. She and most of the people she knows have already been vaccinated – in her case, with the Moderna vaccine. She tells me that the Philippines have prioritised people to be vaccinated in a similar manner to New Zealand, with healthcare workers, older people and those with underlying medical conditions vaccinated first.

The figures from the Philippines are consistent with what we’ve seen in New Zealand. More people have been vaccinated than said they were willing early in the pandemic. Over time, the efforts of health officials and medical professionals, as well as the realities of the pandemic, have convinced not only the uncertain but even some of those who initially were unwilling.

Another country that has faced serious challenges in vaccinating its citizens is Nigeria. I’ve written about vaccination in Nigeria before, because they’ve faced some extreme political opposition to vaccines in the past. In 2003 the political and religious leaders of three states ordered their citizens to refuse the polio vaccine, because they believed it was part of a western plot to sterilise Muslim girls. But Nigeria is also interesting because of the work they’ve done to overcome that opposition and misinformation. They did a good enough job with polio vaccination for the African continent to be was declared free of wild polio last year. In the Covid-19 pandemic, how have they managed? Have they been able to build on the success of their polio programme? Or have the challenges they faced in the polio eradication persisted?

It’s difficult to estimate the impact of the pandemic in Nigeria. Officially, they’ve had only around 220,000 Covid-19 cases, with just under 3000 deaths from a population of over 200 million. However, they’ve only done 3.7 million tests. In comparison, New Zealand has done a total of 5.4 million tests. The limited testing means that the official numbers are almost certainly an underestimate, but there are also demographic reasons, such as a young population, which means that Nigeria, along with many other African countries, has been less affected by Covid-19.

The economic impacts of Covid-19 have been particularly hard on Nigeria, however. In the first months of the pandemic, Nigeria plunged into its deepest recession since the 1980s. The recession was partly the result of Covid-19 control measures, but the collapse in the global oil price also made a major contribution, as oil brings in 80% of Nigeria’s export revenue.

I’m curious to hear more about the pandemic in Nigeria from a local perspective, so I ask a friend whether he can arrange for me to speak to someone there. He puts me in touch with Jeremiah Abednego, an entrepreneur in Benue state, which is south-east of Nigeria’s capital, Abuja. Abednego trained as a biochemist, but he now owns a factory that processes cassava roots into gari, a kind of flour used in West African cooking.

Abednego confirms the economic impacts of the pandemic. He was personally affected, with his business grounded for almost a year because he couldn’t access the raw materials his factory needed. The other most obvious feature of the pandemic, he says, is the arrival of face masks. Nigerians were not used to masks at all, but are now expected to wear them everywhere.

I ask what he knows about Nigeria’s vaccination programme. He’s heard about it – he knows that the federal government has set up a programme and he’s heard of vaccination in some states, but not his own. He hasn’t been offered a vaccine himself, although he plans to get vaccinated when given the chance. He does know people who’ve been vaccinated, but others are determined that they won’t be. In some cases, this unwillingness stems from a mistrust of anything that comes from government. But, he tells me, misinformation is common too. People still believe the myth that vaccines are a western plot to suppress fertility. The problems with misinformation are worse in the north of Nigeria, just as they were during the polio eradication. There, whether people get vaccinated depends very much on what the leaders say. If you can convince the leaders to get vaccinated, the people will follow.

I’ve looked for data online about the percentage of people willing to be vaccinated in Nigeria, and there’s nothing directly comparable to New Zealand and the Philippines. One study, conducted in the south of Nigeria, found that just under half of the people surveyed said they were willing to be vaccinated. Another study found around 66% willing to be vaccinated, although that study was also biased towards people from the south. There’s another catch with both studies too – in both cases they’re biased towards people with higher levels of education, so may not represent the population as a whole.

Even though those surveys don’t give a good representation of the general population, they do show substantial numbers of people willing to be vaccinated. Unfortunately, though, that hasn’t translated into a successful programme so far. In fact, Nigeria’s programme is poor even by African standards. While South Africa has nearly 25% of their population fully vaccinated, Nigeria is sitting at around 3%.

For that, though, it’s hard to blame Nigeria. Like many countries, it has struggled to access vaccines. Now, the vaccine donations are rolling in, but a lot of the donated vaccines are close to expiring. That creates real difficulties in delivering vaccines in a country which is larger than France and Germany combined, and has real difficulties with infrastructure. As a result, Nigeria has had to destroy a million vaccine doses – a frustrating waste when there are so many unvaccinated people. It’s great to see countries who have bought too many vaccines donating them, but that doesn’t make up for the fact that they purchased far more than they needed in the first place. This grossly unfair vaccine distribution has left countries like Nigeria struggling to plan and deliver their vaccine programme. For Nigeria’s sake, and for many other countries where most of the population remains unvaccinated, we need to do better.

You can support the COVAX initiative to deliver vaccines to low and lower middle-income countries by donating to UNICEF here.

The Turnstone will be taking a break for a few weeks over Christmas. I’ll send out my usual “Talking about vaccines” on Wednesday, then the next Turnstone will be on the 16th of January.

Let me know what you think in the comment box below. And if you know someone who might find this article interesting, please share it with them.

Thank you Fiona. The more I hear about Nigeria, the more I realise what a fascinating and complex country it is. And PNG is another fascinating and complex country where vaccine hesitancy seems to be a big issue, although in that case I don't know anything about the history behind it.

Thanks for this article Melanie - so much of what you have written here is recognizable - my husband and I lived in Nigeria for 5 years mid to late 90s. He’s soon to become involved with a COVAX project in PNG and he will specifically be looking at vaccine hesitancy issues there so will find this interesting - thank you