Testing 1, 2, 3

What are the different types of Covid-19 tests, and how do they differ? (8 minute read)

Welcome to The Turnstone. Here, I share my perspective on science, society and the environment. I send my articles out every Sunday - if you’d like them emailed to you directly, you can sign up to my mailing list.

Since the very start of the pandemic, one of the most crucial tools for managing Covid-19 has been testing. While most of us were still in blissful ignorance, right back in January of 2020, scientists in a number of countries, including Malaysia and Germany, were already diagnosing Covid-19 cases using reliable and sensitive tests. At the time, it was a stunning achievement, although we hardly give it a second thought now, as tests for Covid-19 are so routine and commonplace.

But testing is a lot more complex than it first appears, and there is more than one type of test available. It is important to know what the different tests do, and when they are useful, or not useful. That knowledge can help us make better decisions to protect ourselves and others as the Omicron variant spreads around the world.

The original Covid-19 tests, those developed in January of 2020, were direct tests. By that, I mean the test is designed to detect the virus which causes Covid-19. Specifically, these tests detect the genetic code of the virus, and they are known by the acronym PCR, which stands for polymerase chain reaction. PCR tests can be incredibly sensitive, because part of the test involves multiplying pieces of the virus – but I’m getting ahead of myself, because before you can multiply pieces of virus you need a sample to work with. So I’m going to go back to the beginning of a PCR test, which is the now-familiar swab.

I admit that I’m lucky – I haven’t had a cold since the start of the pandemic, and I’ve never had contact with someone infected with Covid-19. This means that I’ve never had a Covid-19 test. But I know people who have, and they tell me it’s not pleasant. A long swab is poked up your nose, taking a sample of material from the very top of your throat. (As an alternative, a sample of saliva can be tested, and there is recent evidence suggesting that saliva testing may be just as reliable as nasal swabs.) The swab is then placed in a tube with some chemicals to prevent any virus material inside from breaking down, and sent to a laboratory. At the laboratory, the sample is cleaned up to remove everything except a molecule called RNA (or ribonucleic acid), which contains the genetic code of the virus. There’s a nice graphic explaining the process in more detail about halfway down the page on this website.

However there isn’t only RNA from the virus left after the cleanup. RNA is an essential part of how cells work, so it’s present in every human cell. And since the swab will have picked up human cells from the top of the throat, there will be human RNA in the sample. There may also be RNA from bacteria or other viruses. The Covid-19 PCR test uses tags, known as primers, that stick only to pieces of RNA from Covid-19. Then, it translates the genetic code that is in RNA into a similar molecule called DNA (or deoxyribonucleic acid), which is more stable and easier to work with. The next step of the PCR test is where the real magic happens – the DNA is multiplied many, many times, to produce millions of pieces of identical DNA. I’ve linked to a video showing the process here.

The final step in the process is to detect the DNA that was translated from the virus’s RNA – if there is any. If there’s no Covid-19 in the sample, then no RNA will be translated into DNA and multiplied in the tagging step, and there’s nothing to detect. The test will produce a negative result.

It’s the multiplication step that gives the PCR test its incredible sensitivity. A PCR test can find a tiny amount of virus. It’s so sensitive that it can detect Covid-19 in the wastewater of a town when just a couple of people are infected, as was the case in Napier recently.

But PCR tests aren’t perfect. Any test can give either a “false positive” – where the test says someone is infected but they actually aren’t, or a false negative, where the test says someone isn’t infected, but they are. False positives are rare, but false negatives are more common. They can occur because something went wrong with sample collection or transport, or because the sample was taken before there was enough virus in the person to detect. Although PCR tests are extremely sensitive, it is possible for an infected person to have too little virus for the test to work.

While PCR tests usually give a clear-cut positive or negative answer, sometimes they give what is known as a “weak positive”. A weak positive case is one where there was so little virus in the sample that even after multiplication the amount was still small. One common reason for a weak positive is that a person has had Covid-19 in the past and there’s still a small amount of virus in their system. It may be that the person is no longer infectious. On the other hand, it could be that something went wrong with the sample, or that the virus is just starting to increase in their body. With a weak positive result, the assumption is usually that the person is infectious. Another test will be needed to confirm the result.

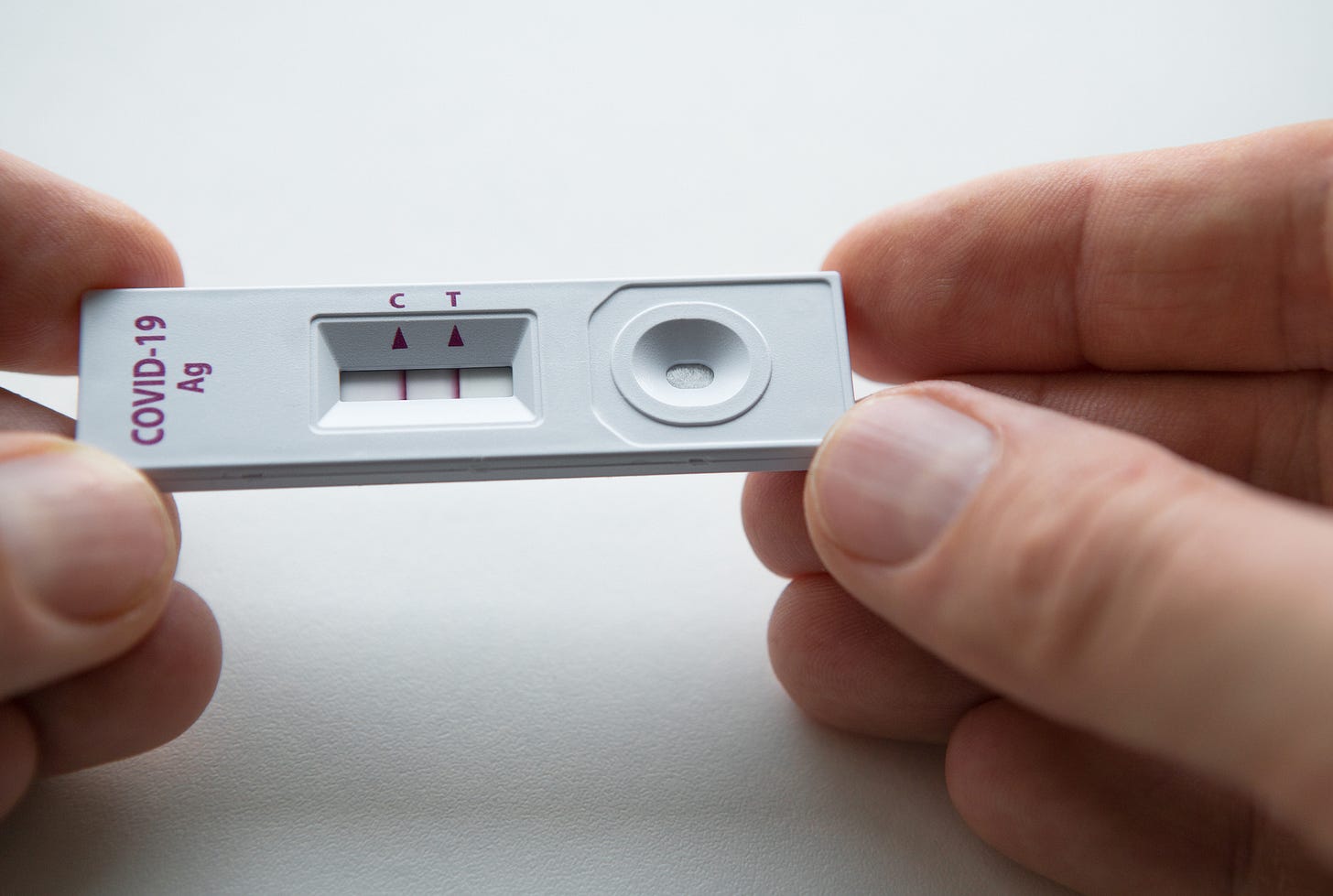

Another type of test for Covid-19 is known as a rapid antigen test. As its name suggests, the test is rapid. While it takes around a day or so to run a PCR test, a rapid antigen test can deliver a result in minutes. Rapid antigen tests aren’t just fast – they are also cheap, and don’t require a laboratory. Instead, a sample (either from a nasal swab or saliva) is placed on one end of a strip of membrane that can be embedded in a plastic frame. As the sample travels along the membrane, it passes across an area containing a chemical that turns red if the spike protein is present, resulting in a red line. Finally, the sample passes across an area containing another chemical, one which turns red on contact with the sample regardless of whether Covid-19 is present, as proof that the test has worked correctly. A positive test therefore results in two red lines and a negative test only one. If no red line shows up, something has gone wrong with the sample. The video I’ve linked here shows the process in a bit more detail.

The rapid antigen test doesn’t contain a multiplication step. This means that the test is only detecting the amount of spike protein present in the original sample. If there’s spike protein present, but not much of it, the rapid antigen test will deliver a negative result. Consequently, rapid antigen tests are much more likely to miss detecting infected people than PCR tests. On the one hand, this isn’t good, because a negative test could falsely reassure someone that they are not infected. On the other hand, rapid antigen tests are great at detecting Covid-19 at the time when a person is most infectious – which is when the levels of virus are at their highest.

Rapid antigen tests can be used as an extra precaution before high-risk events such as air travel, or when people turn up at hospital emergency departments. As long as there are enough available, they can make a real difference for managing Covid-19. The problem is that there’s a global shortage. While it would be nice if we had enough to be using them regularly, I would personally prefer that they were available for use in high priority settings like hospitals everywhere in the world, rather than seeing rich countries monopolise the supply for people attending concerts and festivals. That won’t happen, sadly, but it’s something to aim for.

There’s a third type of Covid-19 test as well, and that’s the antibody test. Antibody testing is an indirect test – instead of looking for parts of the Covid-19 virus, it looks for the body’s response to the virus, in the form of antibodies. Antibodies are found in blood, so antibody tests use a sample of blood. Because it takes time for antibodies to build up in response to Covid-19 infection, it takes longer after infection for a test to give a positive result. Consequently, an antibody test is next to useless at determining whether someone is infected with Covid-19 right now. But they are useful to show whether someone has had Covid-19 in the past. Depending on the specific test, they may also give a positive result in someone who has been vaccinated. However, they don’t measure the quantity or quality of the antibodies present, which means they can’t be used to determine whether or not someone is immune to, or protected from, Covid-19.

As Omicron sweeps the world, and in the future when there are more new variants, Covid-19 tests remain as important as ever. But, as with vaccines, there is ongoing inequality over who has access to tests. This inequality is well-documented within wealthy countries, such as the United States and Britain. It’s a lot harder to find information about inequality between wealthy and less wealthy countries. In fact, I spent some time searching and found very little. And that’s an issue we need to address if we are going to find our way out of the constant cycle of new variants and waves of infection. Because we really need all countries to have the chance to manage Covid-19 effectively, and one part of effective management will always be having the right tests available in every country.

This year, I will be sending out The Turnstone once a week. Every two weeks, I will send an original article, like this one. On one of the alternate weeks I will send out “Talking about vaccines”. On the other week I will share something about climate change, called “Talking about climate change”. The focus will be conversations we can have and actions to take on climate change.

Let me know what you think in the comment box below. And if you know someone who might find this article interesting, please share it with them.

Another well written and informative article. Plus I got to put my Biochemistry education to work.