The lighthouse keeper's cat

One pregnant cat and three endangered bird species - it's not going to end well (4 minute preview, 8 minute full article)

One of the books I remember from my childhood was called The Lighthouse Keeper’s Lunch. It told the story of a lighthouse keeper named Mr Grinling, whose delicious lunch was stolen by a hungry seagull. Every day, Mrs Grinling would pack the lunch into a basket, then send it via a cableway across the narrow straight to the island where he worked on the lighthouse. Every day, the seagull would steal the lunch during its journey across the strait. Mr and Mrs Grinling hatched a cunning plan – to put their cat, Hamish, in another basket beside the lunch, to scare off the seagull. Unfortunately for the lighthouse keeper’s cat, and for Mr Grinling, Hamish was terrified of heights and cowered in the basket while the seagull stole the lunch again. Eventually, Mrs Grinling solved the problem by making extra hot mustard sandwiches for a few days. The seagull decided to steal someone else’s lunch and Hamish was left in peace.

Because of the book, the picture in my mind of a lighthouse keeper’s cat was amiable, ginger and lazy. But when I was older, I heard another story about a lighthouse keeper’s cat. On the island of Takapourewa in the late 19th century, the lighthouse keeper’s cat brought in a strange bird one day. It turned out to be a new species, found nowhere else in the world. Then, the next day, the cat brought in another. Then another, and another. Soon, there were no more birds. This tiny songbird was extinct, wiped out by a single cat.

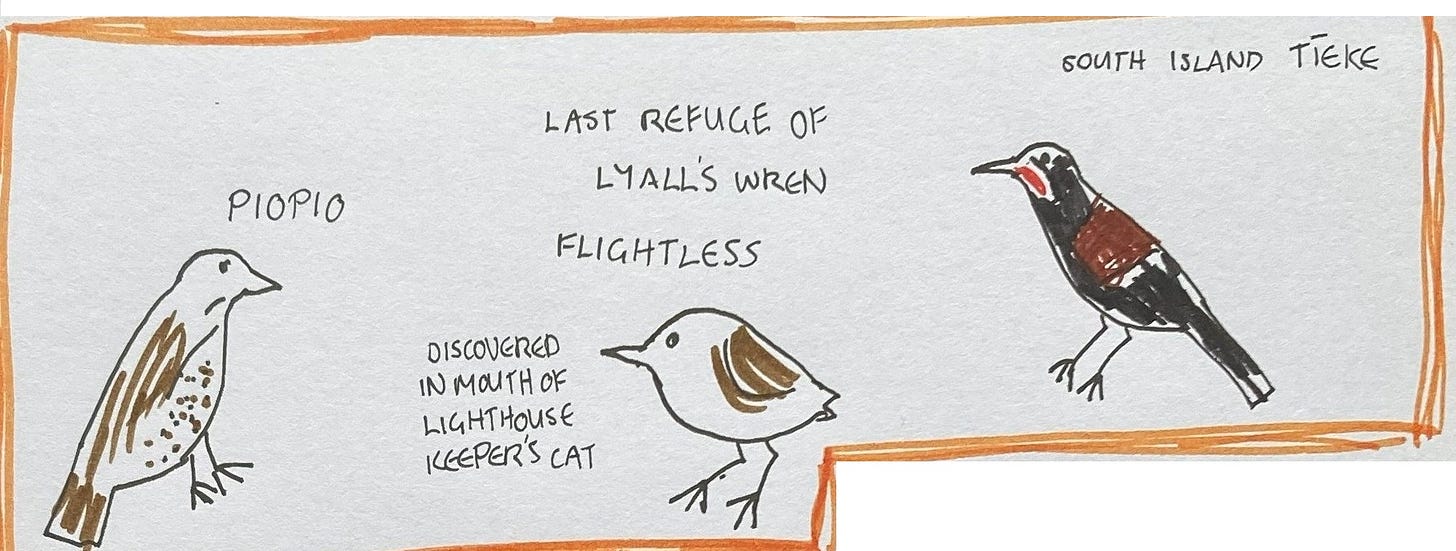

The former story is a work of fiction, but the second story is not far from fact. In the late 19th century, there was a sparrow-sized bird called the Lyall’s wren, or Stephen’s Island wren, found nowhere else in the world but Takapourewa. It had once been found throughout New Zealand, but had probably been wiped out in most parts of the country long before, by kiore, the small rat introduced by Māori. The first specimen of Lyall’s wren to come to the attention of scientists was indeed brought in by the lighthouse keeper’s cat, and so was the last specimen. However, there was more than one cat. A pregnant female was brought there in 1894, and a few years later the island was described as swarming with cats. The wrens did survive for several years, as specimens were being sent to collectors and traders in Wellington, possibly until around 1900. Ultimately, though, cats caused the extinction of this small, flightless bird.

Also present on Takapourewa when the lighthouse keeper’s cat arrived two other endangered birds – the piopio, sometimes called the New Zealand thrush, and the South Island species of tīeke. The piopio was a substantial bird, twice the size of a European thrush, although its markings were similar. It was said to have the most melodious song of any New Zealand bird, but we have to take the word of 19th century authors for that, because it became extinct at the around the start of the 20th century. The Takapourewa birds may have been among the last piopio to survive, but they were gone within a few years of the cat's arrival. The tīeke was also wiped out on Takapourewa, but survived on Taukihepa, off the coast of Rakiura or Stewart Island.

Lighthouse keepers and families lived on Takapourewa until the lighthouse was automated in 1989. For an understanding of what life was like, it’s well worth reading Jeanette Aplin’s account of her six years living there in the 1960s. But even after the lighthouse keepers went, the island was occupied, by Department of Conservation rangers. Their work on the island included weed control and replanting the areas which had been pasture.

As well as the rangers, who would often spend several years on the island, there were regular visits from others involved in conservation work. My own visit was brief compared to many of my other island trips – I stayed only one night. I had to fit in with existing travel arrangements to and from the island, which meant I arrived on a boat carrying various supplies and left on a helicopter with half a dozen Cook Strait giant wētā. It was a short but memorable trip.

The terrain of Takapourewa is not accommodating to humans. Although the terrain on the top is flat enough to walk around, the sides are precipitous. Even some of the flatter areas are inaccessible. Under the canopy of twisted trees, the ground is gouged with seabird burrows. Walk across it, and you risk putting a foot through, at best contributing to erosion, at worst crushing a chick or a tuatara which has co-opted the burrow.

At the time, I had serious doubts about the impact of the difficult terrain on weed control. At some point, the invasive tradescantia must have been a lighthouse keeper’s houseplant, and by the 1960s was well-established in a number of areas. While it had been considerably reduced by the early 2000s, when I visited, the remaining locations were in difficult-to-reach areas.