The shape of an argument

Could a philosophical technique help fight mis- and disinformation? (8 minute read)

If you’d asked me ten years ago what philosophy could do to help my work, I’d have struggled to give you an answer. Although I didn’t work as a scientist, my work was always connected with science. I worked in biosecurity and conservation, both areas which rely on information from biology. I read many papers about plants being damaged by insects and disease, or about what enabled one plant to replace another in a particular area.

It seemed a long way from philosophy. It wasn’t that I saw philosophy as impractical, because I could see that it provided useful insights into how we could live our lives. I could see that it was relevant to important issues such as morality. But how could it connect with pests and diseases of plants? I couldn’t see it.

Then, in 2015, a researcher who had been looking at the challenges facing biosecurity in Australia and New Zealand had a suggestion for us. He said that we should learn a technique called argument mapping. On his recommendation, we invited a former philosophy professor, Tim van Gelder, to teach us.

What we learned was a revelation. I saw people who had been talking past each other for years find common ground. We learned to express what we wanted to say more clearly, and to understand others better. So, I wondered whether some of what we learned on the argument mapping course might also help with spotting climate misinformation and disinformation, or simply resolving where we have different views on what to do about it. I’ll try and refer to online sources where I can, but some of what I’m explaining comes from material I hold in hard copy form. I’ve also put together some information at the end if you want to learn more.

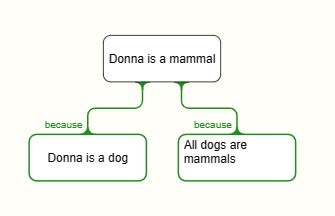

Argument mapping is the process of representing reasoning in a visual form. Here’s a very basic example. As I’ve mentioned previously, and as you’ve probably seen in various pictures I’ve included in this newsletter, Donna is my dog. Simple logic tells us that if all dogs are mammals, then Donna must be a mammal. The argument can be represented in this way:

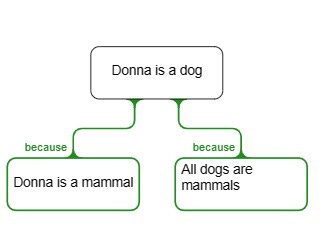

We could rearrange this diagram in a different way, but it wouldn’t make sense.

We can’t conclude that Donna is a dog just because she is a mammal. If we could, we could also conclude that Donna is a cat, because all cats are mammals too.

But how do we know Donna is a dog and not a cat? That comes down to evidence. Here’s a picture of Donna, she’s the one on the right, alongside Bonnie the tabby cat for comparison.

The argument map for that looks like this. The evidence for Donna being the dog is a photo of her, and because I know what a dog looks like.

I could keep going with this, for example by looking at why I think that dogs are mammals, or why I think I know what a dog looks like, but this diagram is complicated enough to explain the principles.

Argument mapping is a technique which helps us clarify and organise our thinking. It helps us to uncover what we assume to be correct, what evidence we have, and where that evidence comes from. It also helps us to understand the arguments that others are presenting to us.

One of the things that we often see in arguments is that some of the crucial points are missing. For example, there might be a statement that all dogs are mammals, therefore Donna is a mammal, but there’s no way you could know Donna was a dog unless I mentioned it. Donna is in the conclusion, but not in the arguments or reasons supporting that conclusion. It means that this argument map breaks one of the rules of argument mapping, which is that everything in the conclusion must appear in the reasons supporting that conclusion. It’s known as the rabbit rule – basically, you can’t pull a rabbit from a hat unless the rabbit is in the hat already.

Putting argument maps together is fiddly and complicated, and it’s something which takes a lot of practice. It’s a worthwhile skill for anyone who does analytical writing, such as public servants who write documents about regulations and policy. It has been demonstrated to improve critical thinking skills in a number of studies. However, it’s not something which can be picked up from reading one article, and I’m not aiming to teach it here. I’ve included resources at the end if you want to know more.

At work, we didn’t routinely do argument maps, but we did use a technique which was based on argument mapping, and that is what I want to talk about in more detail. The technique is known as CASE (or, more formally, the CASE schema). The letters stand for:

Contention, which is the main conclusion

Argument, a claim which supports or opposes the contention

Evidence, factual information which backs up the argument (there can also be counter-evidence which disagrees with the argument)

Source, where the factual information came from

You probably noticed that I wrote them in the order Contention-Argument-Evidence-Source, which spells CAES, but it’s usually written as CASE. Since we are talking about climate change, here’s an example which I’ve created based on reasoning I’ve come across many times in discussions on climate change:

Contention: humans aren’t causing climate change

Argument: the climate has always changed

Evidence: there have been a number of periods where the Earth was much warmer than today, including Cretaceous Hot Greenhouse about 92 million years ago, and the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum about 56 million years ago

Source: NOAA, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

I consider information provided by NOAA to be reliable, even if it’s just their public communications rather than research papers, so I have no issue with the source for this example. I can also verify the evidence from numerous other sources. The evidence that the Earth has been much hotter than it is today certainly supports the argument that the climate has always changed. But there is a problem in the link between the argument and the contention – an unstated assumption. This particular example of reasoning assumes that because humans didn’t cause climate change in the past, they also couldn’t be causing climate change today. That’s not necessarily correct. There are lots of things which have always happened, such as floods. This doesn’t mean that humans don’t also cause floods by cutting down forests or building channels which allow storm surges to overwhelm cities built below sea level.

Sometimes the contention and arguments hold together logically, but the evidence or sources have problems. I read my way through an exchange on Facebook between two people who seemed to have a lot of time on their hands. One made the statement:

There is no climate crisis. There is no real evidence that CO2 has any effect on our global climate. The AGW hypothesis has been falsified by science.

The last sentence is a bit unclear, but in the context of climate change, AGW means “anthropogenic global warming”, meaning climate change caused by human activities. Saying it’s been “falsified by science” is basically suggesting that science says it’s untrue. Put into a CASE structure, it looks like this:

Contention: there is no climate crisis

Argument: the AGW hypothesis has been falsified by science

Evidence: there is no real evidence that CO2 has any effect on our global climate.

Source: not given, but in follow-up posts in the conversation the author referred to two books

As a piece of reasoning, this does hold together. If there was no evidence that carbon dioxide affected the climate, that would substantially weaken the argument for climate change being caused by human activities, and would support the conclusion that there was no crisis. However, the other person involved in the discussion disputed the evidence and sources, and quoted a recent and credible paper in support of their view.

It's also worth applying this approach to statements we agree with – after all, there’s always a risk that confirmation bias makes us overlook flaws. Here’s one rather silly example, which I also found on Facebook.

The munitions and nuclear weapon tests used in various wars are responsible for the increase in global temperature. Cutting of trees should be stopped and new trees should be planted.

This one’s actually quite hard to put into CASE, which can be a warning in itself. What is the contention? I think it’s probably the author’s suggestion that we should stop deforestation and replant more trees. I broadly agree with that statement. I also believe that war and nuclear weapons testing are both harmful. However, I can’t see how it all holds together.

Contention: we should stop cutting down trees, and new trees should be planted

Argument: munitions and nuclear weapons tests are responsible for global warming

Evidence: ??

Source: ??

Resources on argument mapping and CASE

This is only a brief introduction to the topic, but I hope that it may interest some people enough that they look into it further. Some of the resources I have previously used are no longer available, but there are still some good sources online.

The following interview with Tim van Gelder gives a good explanation of the topic.

Tim van Gelder - Argument Mapping & Intelligence Augmentation (youtube.com) (22 minute video)

Tim is part of the Hunt Lab at the University of Melbourne, where they teach both argument mapping and CASE, for those who have a professional interest in the subject.

Hunt Lab Home (unimelb.edu.au)

There’s a lot of free material on the websites for Rationale, which is a software tool developed by Tim van Gelder for creating argument maps. I’ve linked to a series of tutorials, and you can use a basic version of the software for free.

There’s also the ReasoningLab website, which is connected to Rationale, but has some additional resources.

There’s a whole free video course with a lecturer from the University of Wisconsin. The image quality isn’t great, but the content is there.

Argument Mapping 1 - What it is and Why it's Great (youtube.com) (10 videos, most around 10 minutes)

In my opinion, your recommendation to look in philosophy for direction on logical discussion is a very good one. A modern philosopher is Sven Ove Hansson who writes very clear and accessible articles on many topics as well as what you are discussing here. Epistemology is more or less central to your discussion and I guess another interesting direction is provided in Hansson, Sven Ove. "Social constructionism and climate science denial." European Journal for Philosophy of Science 10, no. 3 (2020): 37. which can be accessed directly from Google Scholar. A rather interesting article he wrote is Hansson, Sven Ove. "How not to defend science. A Decalogue for science defenders." Disputatio 9, no. 13 (2020): 197-225. One can see ties between the first article, a rather detailed exposition, and his "decalogue". A very interesting article is Hansson, Sven Ove. "Can uncertainty be quantified?." Perspectives on Science 30, no. 2 (2022): 210-236. but it is not available without subscribing to a service but should be accessible with a public library card:)

In my personal opinion, much of the "push back" on climate change has not necessarily been against technological or scientific claims but rather a perspective that realistic operational solutions have not been proposed. That is in my opinion, the opposition to the scientific claims is less about whether or not the science is telling us how nature will respond and more about providing solutions that can actually be implemented. My current (and fluid) perspective is that it is possible the populists Hansson and others point to who "push back on/deny" the climate change agenda do so because, although they may accept the problem exists, those who bang on are doing nothing more. What is needed at this point are practical solutions.

What must be faced is that the current, really staggering, worldwide energy consumption is approximately 420 exajoules annually and rising. Effectively all of that energy comes from burning (let's say oxidizing) fossil fuels in various forms. The atmospheric carbon dioxide storage, or buildup is shown graphically in Houghton, Richard & Goodale, C.L.. (2004). Effects of Land-Use Change on the Carbon Balance of Terrestrial Ecosystems. Ecosystems and Land Use Change. 85–98. 10.1029/153GM08. (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228849045), Figure 2. They point out that the models used in the analysis are subject to high uncertainty but nevertheless, even if they were substantially wrong, there would still be a relatively large (and growing) amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Although much less so than direct combustion, it is somewhat interesting that changes in land use appears to be a problem as well (as shown in Figure 2). I guess most everyone, certainly there are a few not on board, can agree on increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide as a matter of observation but what I guess we most disagree about is, given the scale of energy requirement, what to do about it.

In summary, from what little I know, there is an ever increasing buildup of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Additionally, from what I know, there are no practical solutions that would completely or even substantially offset the fossil fuel contribution especially if all effects (pollution, economics, environment) are considered important. My opinion again from the little I know, is there may be some things out on the horizon such as nuclear fusion that could offer: 1) negligible land use (very small footprint) and therefore can be distributed; 2) non-polluting (can be a problem in D-T due to tritium but p-B11 gets around that); 3) it can be designed to operate continuously (like fission reactors) and ; 4) can be arbitrarily scaled and located almost anywhere. Unfortunately, fusion has been five years from reality for the last several decades, although the Fusion Industry Association (FIA) puts out encouraging news (https://youtu.be/R45jMWhjwRk?si=H2lD5tpdiJpNkhQH) from time to time. Nevertheless, even if fusion becomes operational, there will be many difficulties to overcome not the least of them how to capture the incredible energy content that can be had in a gas tank moving around with an automobile, for one example. Oh well ...

Fabulous instruction. Thank you so much. I am sharing it with my wider whanau. We learnt this method of reasoning in basic essay writing technique in the 70s . Thank you Melanie. This is an important lesson for us all.