Under the microscope

Appreciating some of the tiniest plants (3 minute preview, 6 minute full article)

I remember my fascination when I noticed something strange growing on the bare clay outside the window of my childhood bedroom. That particular spot was tucked into a corner, with the walls and concrete foundations of the house on two sides. An oak tree, much older than the house, shaded it from the east. Since the spot was under the eaves, rain would only reach it if it came from the north-east. In summer, the clay would bake solid and crack. In winter, water dampened the surface and ran off into the cracks, rather than soaking through. No grass would grow, nor any of Auckland’s many weeds.

But I looked closely one day in early spring, and realised that something was growing. There wasn’t much to it, a shapeless green film creeping over the clay surface. The film was punctuated with small spikes, no more than a centimetre high. I’d never seen anything like it.

I had found one of the more obscure types of plants, commonly known as a hornwort. Those who have dealt with aquatic weeds in New Zealand are probably familiar with a submerged plant known as hornwort, as it is one of the worst aquatic weeds we have. The hornwort I had found, however, had nothing to do with the aquatic weed – that they shared a common name was simple coincidence.

Plants growing on land fall into two main groups, with a few exceptions. One group is broadly termed vascular plants, from the Latin words for channel: vas or vasculum. Just as we have a network of blood vessels which carry blood around our bodies, vascular plants have a network of tubes which transport nutrients and water. Almost all the plants we notice around us are vascular plants: trees, fruit and vegetables, the flowers in our gardens, giant conifers such as kauri and redwood, grasses, ferns.

But there’s another group of plants, one which most of us pay less attention to. I’m certainly guilty of this, because although I find them fascinating, I’ve never learned to identify them properly. Lately, though, I’ve been trying to learn more about them. I’ve been taking more photographs and attempting to learn some names, although that’s still a work in progress.

So, I thought I’d share some of what I’m learning. I don’t have any drawings of them yet, but that’s something I’m planning to do in future.

There are various ways of describing these plants, but I’ll focus on the most obvious. These are the plants which aren’t vascular plants, the ones which lack the network of tubes carrying nutrients and water. Without this network, they are unable to move nutrients and water efficiently, which limits their size. So, non-vascular plants are small.

The most well-known of the non-vascular plants are the mosses. However, like the term hornwort, the term moss can also deceive. For example, the plant known as “Spanish moss”, which festoons trees in parts of the southern USA, is not a moss. It’s actually a cousin to the pineapple. However, there’s a plant which looks very much like it in some wet New Zealand forests, and this actually is a moss.

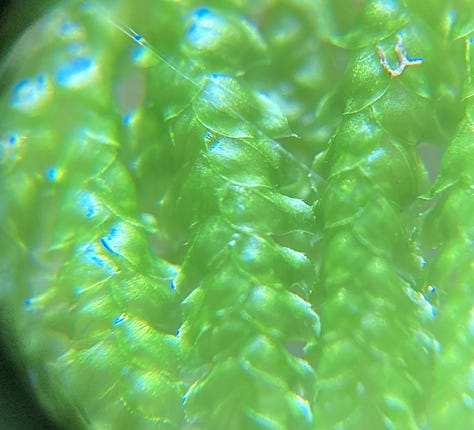

Up close, many mosses look similar to vascular plants. They have a stem and leaves, and they attach to their substrate, such as a tree branch or rock, by fibrous filaments which look like roots. However, the filaments aren’t roots, because their main function is not to absorb nutrients, but simply to attach the moss to the substrate. Water and nutrients are absorbed directly by the leaves.

Hornworts, in contrast, look nothing like a vascular plant except for their green colour. They simply grow outwards like a spreading blob on a surface such as stone (or compacted clay). The blobs do have a structure, though, and are quite solid. The top layer contains the cells which make the plant’s food from sunlight, while the underside has filaments which attach the blob to the surface it’s growing on. The spikes I saw growing on the blob outside by bedroom window were the reproductive structures. I’ll come back to these in a moment.