Blotted copybook

On the trail of science's dirty secrets with Elisabeth Bik (12 minute read)

It was the simplest of experiments, but it changed Elisabeth Bik’s life. This experiment wasn’t done in the prestigious laboratory where she conducted her microbiology research. There was no complicated study design, no microbe cultures or chemicals, and no expensive instruments, apart from her laptop computer. One evening she typed a sentence from one of her publications into Google Scholar, the specialist version of Google used by researchers. The result left her shocked and angry.

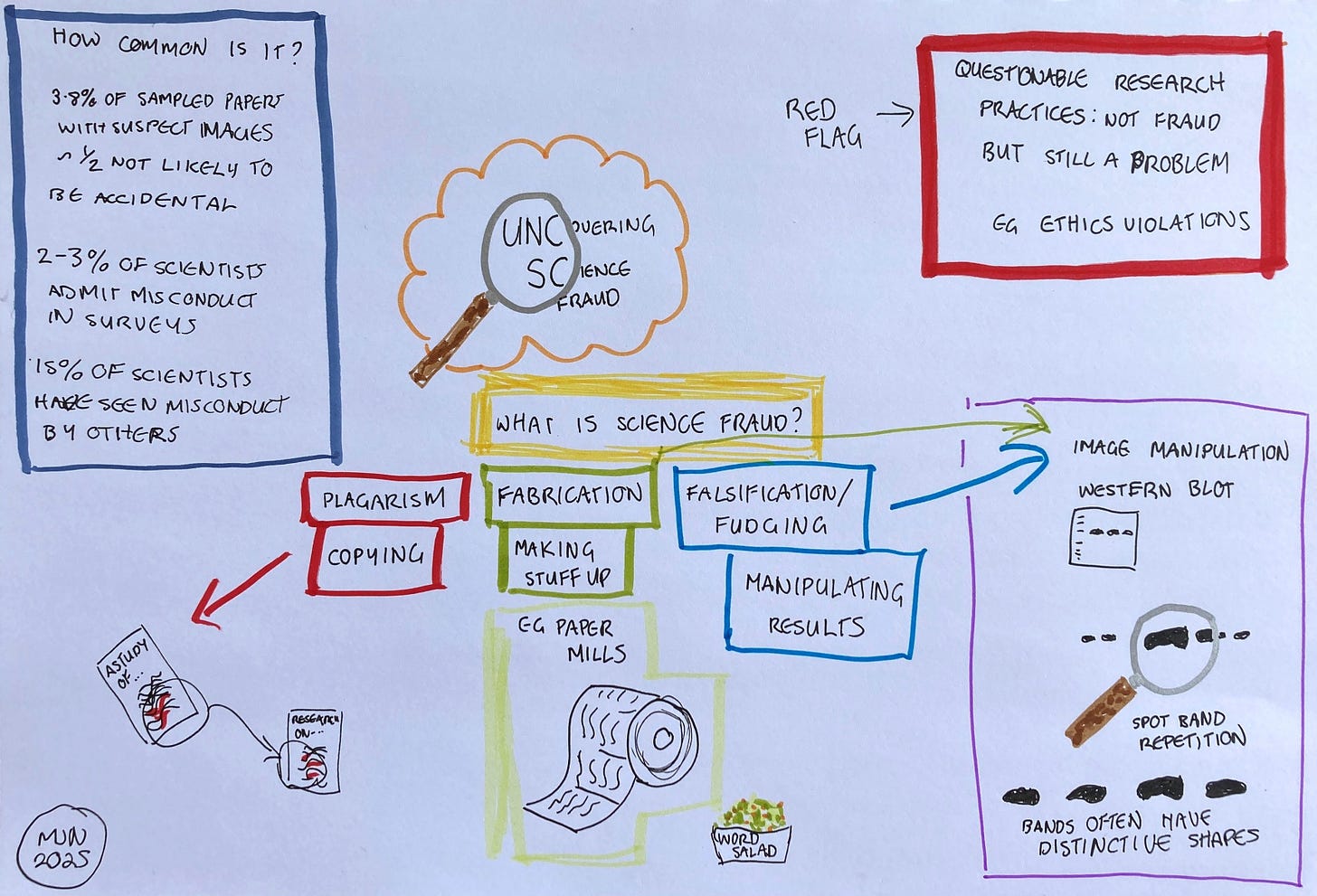

She discovered that some of her work had been reproduced, verbatim, in another publication. So too had the work of other scientists. None of their work had been acknowledged. She’d uncovered an example of plagiarism, a kind of scientific fraud. The discovery set her life on a new course and now, more than a decade later, Elisabeth is a recognised expert at detecting fraudulent science. She has identified thousands of suspect papers, leading to more than 1500 being retracted. Her work has drawn both accolades and attacks.

How does a microbiologist end up as a science fraud sleuth? Why does she keep doing it when it’s made her a target for harassment and even lawsuits? What’s the scale of the problem? And what can we do about it? These questions have interested me since I first came across her work. So, when I saw that she was visiting Wellington and giving a talk, I immediately signed up to attend. I also sent her an email to see whether she’d speak with me, which she very generously did.

Until the day of her fateful plagiarism experiment in 2013, Elisabeth’s career was typical of many scientists. She developed an interest in the natural world as a child, and was drawn to microbiology because of an inspirational professor, who later became her PhD mentor. She specialised in studying the microbiome, or microbe communities, of humans and marine mammals.

Elisabeth was prompted to conduct her simple plagiarism experiment after listening to a podcast. It made her curious. Had anyone ever plagiarised her research? So, she conducted her experiment. “If I’d picked another sentence, I wouldn’t have found anything. I just happened to grab a sentence which had been plagiarised. I immediately went into detective mode. I found that it wasn’t just one sentence. It was two and a half paragraphs or so of my text. Other paragraphs in the same publication had been plagiarised from other sources.”

The dishonesty outraged her. She believed in the value of science for finding the truth. Scientists build on the work of other scientists – with appropriate acknowledgement. Stitching together a patchwork of stolen sentences from other authors wasn’t science.

She began digging further, unearthing other examples of plagiarism and reporting them to the publishers. Soon, the slow, careful detective work of identifying plagiarism became her hobby. “Other people were watching Game of Thrones, and I was doing this.” She would enter sentences into Google Scholar, and if something suspicious came up, she’d begin analysing and dissecting the paper. “It’s almost sentence by sentence. Once you have a sentence that has been plagiarized, you type in other sentences from the same paper, and you might find they’ve stolen from other papers too. It’s like pulling a thread where one sentence that had been stolen leads to two others, and then each of these two leads to five others and it branches out to an enormous number of papers. I try to focus on the ones which have more than 50% of the text plagiarized. That couldn’t possibly be a mistake, something which was left in by accident.”

While she was investigating plagiarism, Elisabeth discovered a talent for unearthing another, very specific, type of scientific fraud. She had always been good at pattern recognition, noticing the patterns on tiles, wallpaper or flooring panels. One day, she was looking at a PhD thesis which contained plagiarism and noticed the same image appeared more than once under different labels. So, she started looking more closely at the images in suspect papers.

The kinds of images she most often studies are known as Western Blots. These look like black bands on a white background and they are used to analyse the many different kinds of proteins found in biological samples. The position of the bands in the images is what most scientists pay attention to, as it indicates the size of the protein or protein fragments. But the bands also have subtle variations in shape, and the backgrounds vary too. The shape and background variations aren’t important to the scientific conclusions, so most people don’t notice them, but they allow someone like Elisabeth to detect duplication and manipulation.

Sometimes, Elisabeth finds the same image is used more than once, but under different labels. This could result from a genuine error rather than dishonesty, but it’s still a problem which needs to be corrected. Other duplications are less likely to result from error. The same image might be mirrored, rotated or cropped, then used multiple times in a paper. Sometimes, distinctively shaped bands or background features may appear more than once in the same image.

She’s found similar kinds of duplication in other types of images too, from microscopic images of human or animal tissue, to dots scattered on graphs to photographs of archaeological sites. While most of her work is on biomedical papers, it appears that no field is immune to these kinds of image manipulations. But how bad is the problem?

In her early days investigating suspect images, Elisabeth spent her spare time checking a set of 20,000 papers for the various types of image duplication and manipulation. Two other highly experienced scientists, working independently from each other, reviewed her findings, and an image was only considered suspect if they both agreed. Their study found that 3.8% of the papers had suspect images, and at least half of these had features suggesting deliberate manipulation rather than error.

Other attempts to estimate the scale of the research misconduct have used surveys of scientists or studies of the number of retracted papers. Both approaches have shown wide variability. A 2009 study which looked at 18 different surveys found that around 2% of scientists reported engaging in research misconduct at least once. A 2020 study which covered the surveys used in the 2009 study as well as more recent surveys found a figure closer to 3%. However, that same study found that more than 15% of scientists reported seeing someone else engaging in research misconduct.

Another way of measuring the problem is to look at the numbers of publications which are retracted, meaning the paper is withdrawn because either the authors or the publisher have recognised serious flaws in the paper. The most common reason for retracting a paper is either honest error or misconduct, depending on which study you look at. What authors do agree on is that retraction rates are rising. A 2024 paper which looked at European biomedical research found that in 2000 there were around 11 retracted papers for every 10,000 published, and that this rose to nearly 45 per 10,000 in 2021.

All of these figures suggest that research misconduct is not insignificant, but still relatively infrequent. However, some areas have been disproportionately affected, and the problem is growing. In 2022, the organisation Retraction Watch, which tracks the retraction of papers, began reporting on mass retractions, where publishers would retract a number of related papers, sometimes hundreds, at the same time and for the same reason. Many of these retractions are of papers in the medical field, although it’s the Journal of Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems which holds the record, at 1561 papers. The publisher which holds the record is Wiley, through its subsidiary company Hindawi, which retracted more than 8000 papers in 2023 alone.

Many of these mass retractions, including the staggering numbers from Hindawi, result from the activity of paper mills. These aren’t literal mills creating paper from wood pulp. They are groups of people whose business is creating fake scientific papers and getting them published in journals from reputable publishers. They are a particular problem in China, due to perverse incentives in their health system, but they also exist in other countries.

Paper mills produce papers which are little more than word salad garnished with recycled or fake images. They are certainly contaminating the body of scientific literature and a serious real problem, but some cases of science fraud and misconduct have been much more consequential.

By early 2020, Elisabeth had left her microbiology research behind and was working as a science integrity consultant, effectively working as an independent science fraud sleuth. It was also the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and scientists everywhere were scrambling to find answers.

In March 2020, Elisabeth’s attention was drawn to a paper from a research group in France. The chances are that you’ve heard about this paper. It suggested that the drug hydroxychloroquine could be useful in treating COVID-19. This paper prompted a flurry of research on the drug, most of it small-scale and poorly coordinated. The then US president and some media outlets promoted it, and it was prescribed to hundreds of thousands of people despite the limited evidence and potentially serious side effects. People who needed the drug to treat their autoimmune disorders couldn’t get hold of it.

However, a number of people expressed concerns about the paper to Elisabeth. So, she tells me, she dived in.

Within a few days of the paper being published, she’d identified numerous problems. There was the lightning-fast acceptance of the paper by the journal, within 24 hours, suggesting there had been little time spent on peer review. The Editor-in-Chief of the journal worked at the institute where the research was conducted and was listed as a co-author on the paper. There was the ethical approval, which seemed to have been obtained after the study was started. She points out that people were more lenient about some rules because of the urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic, but the problems didn’t end there.

Among the most important problems were the exclusion of certain patients who received the drug and the differences between the groups of patients who received the drug and those who didn’t. There were originally 26 patients receiving hydroxychloroquine treatment, but the data were only used for 20, because 6 didn’t complete the treatment. Why not? In four of those cases, it was because they became sicker – three were transferred to intensive care and one died. The patients who received the drug were also in a different hospital or clinic from those who didn’t. She tells me: “we learned later that some of those who received hydroxyquinoline just had to stay at the clinic for an hour, and then they could leave again. The paper implied that they had been in the hospital for a couple of days, but they actually walked in and out each day, so they weren’t that sick. But the untreated patients were in a real hospital.”

There were more issues with the paper – you can read her analysis here – but that one paper prompted her and other science fraud sleuths to look more closely at the whole laboratory. The closer they looked, the more problems they found. The head of the laboratory, Professor Didier Raoult, was one of France’s most trusted voices on COVID-19, if not the most trusted. Yet the sleuths were uncovering problem after problem, not just in the paper on hydroxyquinoline, but in many papers from his institute. There was evidence of image duplication and manipulation. There were 17 papers published over 10 years which referred to the same ethics approval number, despite being very different studies. All were conducted on people living in homeless shelters, making them a vulnerable population who would require a higher standard of care to ensure they were treated ethically. Then there were the 23 papers with the same French ethics approval number which were based on samples collected from people in Africa. These papers listed co-authors from France, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia, but none from the countries where the samples were collected.

Elisabeth wasn’t alone in uncovering these issues. When we speak, she particularly credits Fabrice Frank, a former biologist who now works as an information technology consultant. Journalists also began asking questions, and many people, some anonymous, pointed out issues on the website PubPeer1. For their efforts, they were insulted, harassed and threatened by Professor Raoult and his supporters. Elisabeth was targeted more than most. Her home address was shared online and in 2021 Professor Raoult and one of his colleagues filed a legal complaint, which was dismissed in 2024.

As of October 2025, Retraction Watch reports 46 retracted papers with Professor Raoult as a co-author. This doesn’t even put him in top ten for most retracted papers – that dishonour currently belongs to disgraced German anaesthesiologist Joachim Boult. More than half of his 400 publications have been retracted since concerns were first raised about his work in 2009. As valuable as science is for answering important questions, the flaws in the system can’t be ignored. So what can be done?

Elisabeth points out that quality control for scientific papers shouldn’t all fall on peer reviewers. The journals themselves need to do more, and employ staff to check for the kind of problems which shouldn’t need an expert peer reviewer to recognise. She gives the example of a study on prostate cancer where half of the participants were women. The same journal had a study on ovarian cancer where half of the participants were men. “If you buy a new phone and it fails the next day, you go back to the store, right? You expect the thing to work in the first place, and as a customer you expect to be helped if you have a problem with it. Publishers need to provide that quality control and customer service.”

For those who work in scientific fields, Elisabeth suggests being more suspicious. “Don’t take things for granted. If you get a paper to peer review, consider the possibility that it could be completely fake. I’m not suggesting everything is fake, but just consider the possibility.”

If you’d like to learn more about flawed or fraudulent science, and the work of science fraud sleuths, here are some sites to check out.

Science Integrity Digest

Elisabeth Bik has a blog where she shares some of her work, the Science Integrity Digest. It includes detailed information about identifying questionable images, as well as the problems with the research on hydroxyquinoline for COVID-19.

Retraction Watch

The group Retraction Watch works under the umbrella of a not-for-profit organisation called the Center for Scientific Integrity. Their website contains a number of resources, including the Retraction Watch database of retracted papers. There’s also a leaderboard for authors with the most retractions, a list of the most-cited retracted papers and a blog outlining various issues with scientific integrity.

For Better Science

The site ‘For Better Science’ collects news of science fraud and other misconduct. It has a number of alarming but entertaining articles by the New Zealand science fraud sleuth known as Smut Clyde.

If you aren’t familiar with it, I have previously written about PubPeer and how to use it to recognise when there are issues with papers. What can we do about suspect science? by Melanie Newfield

Wow! OK, a few things:

1. "Journal of Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems"???

2. I'd think AI would be really helpful with identifying fraudulent papers and plagiarism -- hopefully this will save Elisabeth some time and energy in the future.

3. When I was a teacher about 20-25 years ago, we had a demonstration of new technology at our PTO meeting (parent-teacher organization -- probably 200 people in attendance). It was the early days of the internet, and the company representative showed how "easy" research could be now by proceeding to copy and paste sentences and paragraphs from websites in order to "write" a paper. I was livid, and spoke to them afterward, but now I regret not saying something in front of the entire group. I wonder how many young people grew up from that era thinking that copying a sentence here and there was how "research" was done?

Regardless, it doesn't excuse the blatant trickery you describe here. Great article!