Get ready to VOTE!

It's the 2025 International Invertebrate of the Year (4 minute preview, 9 minute read)

This week, I decided to indulge myself. I was checking social media when I should have been doing something else, and saw something which sent me off on a tangent, like a magpie which has spotted something shiny. You see, I saw that The Guardian had released their shortlist for the 2025 Invertebrate of the Year. A couple of months back, I had seen them requesting nominations, and so I had sent something to them. When I checked the shortlist, it turned out that I wasn’t the only person to nominate this particular creature. It had made the cut.

So, instead of writing about plants, which was my original plan, I decided to share my delight and write about the humble tardigrade, also known as the little water bear or the moss piglet. I hope that you may then decide to vote for it when this important poll opens on the 2nd of April. Since they are only accepting votes for two days, I will send out a brief reminder on the 2nd, once voting is open, and include the link.

If you are asking yourself what on earth is a tardigrade? you won’t be alone. They are microscopic, so most people have never seen one. In fact, I haven’t myself, but that doesn’t take away from the fact that I think they are fascinating.

Before I get to tardigrades, I should probably explain about invertebrates, as the term isn’t self-explanatory. We generally divide animals into vertebrates, which are animals with skulls and backbones, and invertebrates, which are without skulls and backbones. We are vertebrates, as are other mammals, birds, lizards, frogs and fish. Some kinds of fish are marginal but still considered vertebrates, such as hagfish. These have a skull but only a rudimentary backbone. However, cuttlefish are not, allowing the flamboyant cuttlefish to be on the 2025 Invertebrate of the Year shortlist as well.

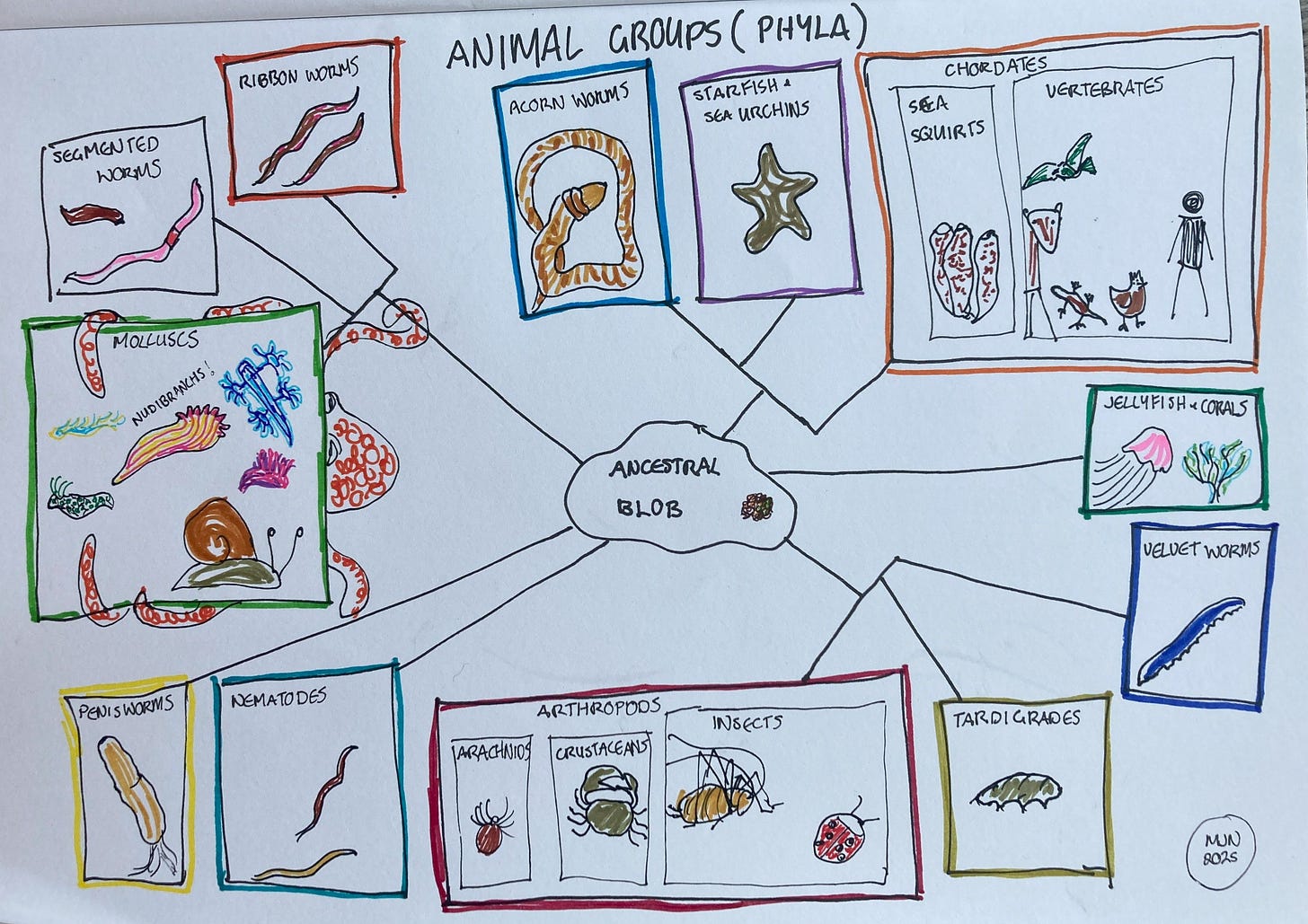

The vertebrates are a distinct group of animals, but the invertebrates aren’t. They are simply any animal which isn’t a vertebrate. The term is a hangover from classifications which saw humans as the most important of the animals, and the animals which were the least like us, such as worms or beetles, as less important. However, scientific classification is no longer based on such perceived values. Instead, it’s based on the family tree of life, with groups classified based on shared ancestors – effectively the classification shows the history of how each group evolved. To be considered a valid classification, all members classified in the group must share a common ancestor, and the common ancestor must be exclusive to that group.

Invertebrates do all share a common ancestor, although you have to trace the family tree a long way – back to a geological period known as the Cryogenian, more than 600 million years ago. The problem is that this ancestor is also our ancestor, so it’s not exclusive to invertebrates. It’s the ancestor of all animals. What that ancestor was like is hard to know – there are no fossils. It probably looked like a blob of cells, but the cells would have been organised. There would have been different types of cell in different parts of the blob, and the cells must have had a way of communicating with each other.

There is, in fact, an animal alive today which may represent what this ancestor may have looked like. It’s known as a placozoa, and I learned about it only when I was trying to figure out exactly what constituted an invertebrate. For more than 200 years, scientists recognised only a single species, although recent genetic studies suggest there might be a number of very similar species.

The majority of invertebrates, as well as all vertebrates, belong to a group of animals which have a single line of symmetry for at least a part of their life1. Even within this classification there is extraordinary diversity. The vertebrates sit within a group called the chordates, which also includes sea squirts. These look a little like a sea anemone which has pulled in its tentacles, but they are about as far as it’s possible to get from sea anemones on the animal family tree. Since they don’t have a skull or backbone, sea squirts are technically invertebrates, even though they are in our part of the animal family tree.

Also close to us, but still invertebrates, are starfish and sea urchins. Even though they can have several lines of symmetry as adults, in their juvenile stages they have only one, which is why they are classified in that part of the animal family tree. We’re also quite closely related to the acorn worms, a group of marine animals which mostly live in sediment and feed on detritus. They are supposedly named for the resemblance of their head to an acorn, but that wasn’t the first thing which occurred to me when I saw a picture of one, and I’m a botanist. I’ll let you be the judge of that (see diagram).

The two largest groups of invertebrates are the molluscs, the group which includes snails, and the arthropods, the group which includes insects. However, both groups are much more diverse than it might first appear. While the familiar garden snail is a mollusc, so too are the smartest of the invertebrates – octopuses, squid and cuttlefish. There are the familiar marine shellfish, giant clams, various types of pond snail and the New Zealand kākahi, which spend part of their life attached to the gills of fish. Oh, and don’t forget the nudibranchs, a group so fabulously colourful they could hold their own against a drag show2. The arthropods are characterised by their jointed legs. It’s a group which includes an astounding array of leggy creatures – insects, spiders, mites, centipedes, millipedes, slaters, crayfish, shrimp, crabs and many more.