Let us prey

Global trade and the disappearance of a childhood treasure (11 minute read)

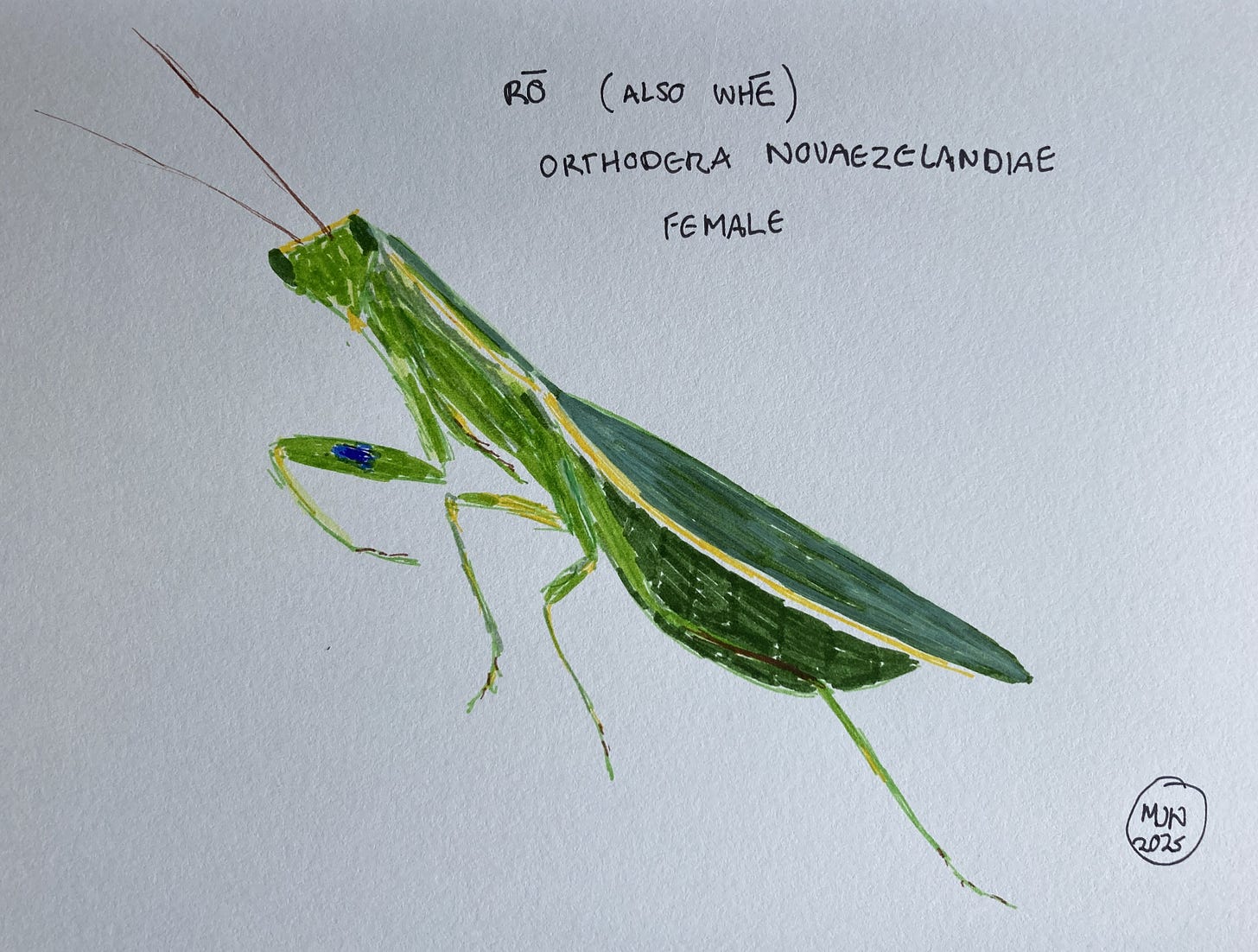

New Zealand’s native praying mantis occupies a special place in my memory. I’m not sure how old I was when I first noticed one, perhaps only five or six, but they were the first insect to capture my mind. For a child curious about the natural world, they were perfect. They are large and distinctive – if you spot one among the leaves, there’s no mistaking what it is. They’re easy to handle, if you are gentle, as they’re not inclined to jump, run or fly away. I remember looking at them closely and being delighted by their intelligent faces, the startling blue of their ears and the dainty way they held their front legs.

They weren’t hard to find when I was a child. Their egg cases were common on tree trunks, fences and the walls of my house, and I’d often see both adults and juveniles in the garden. I’d pick them up, admire them, then place them gently back where they’d come from, my day feeling a little brighter. It never crossed my mind that they’d be gone within a few years.

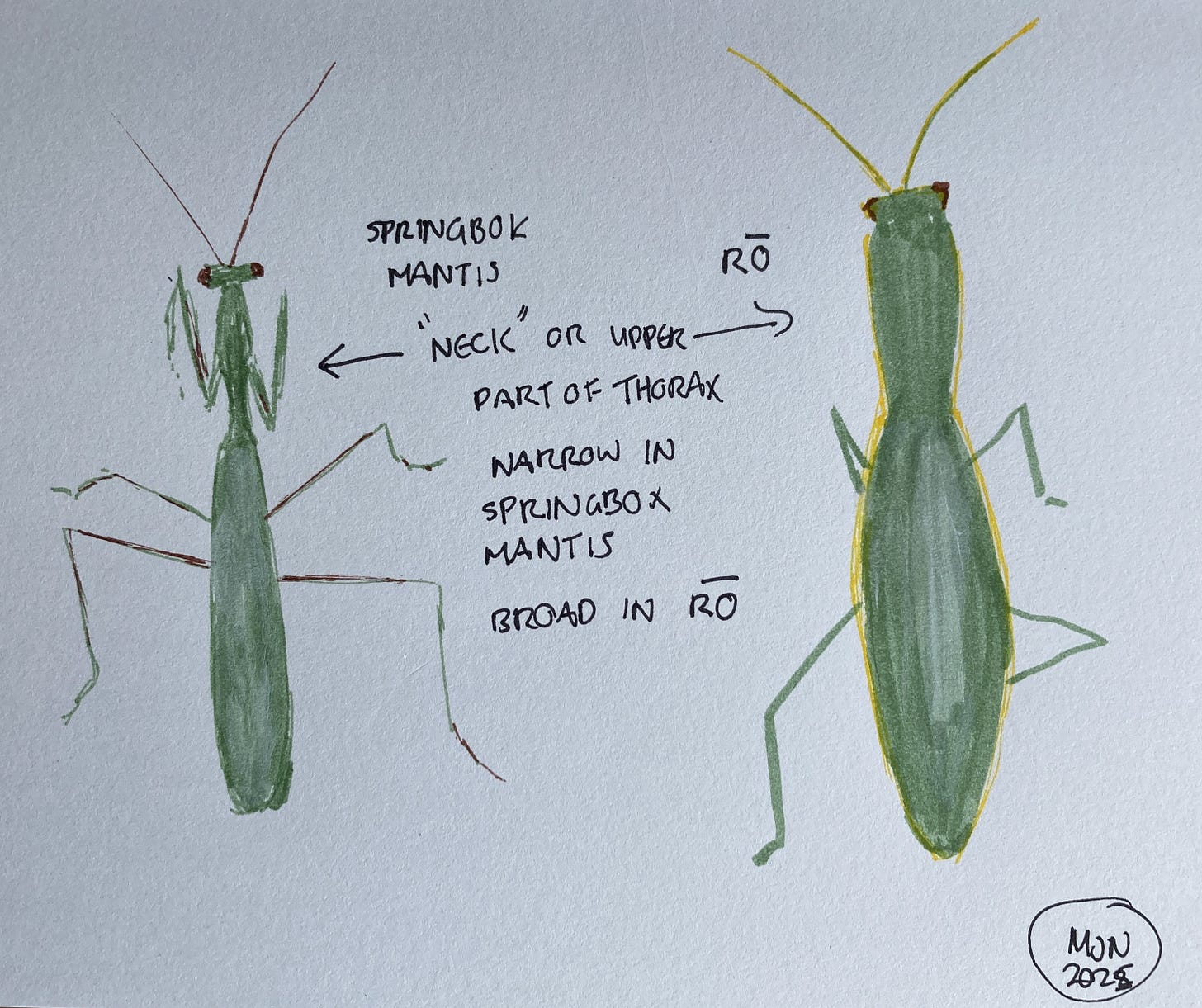

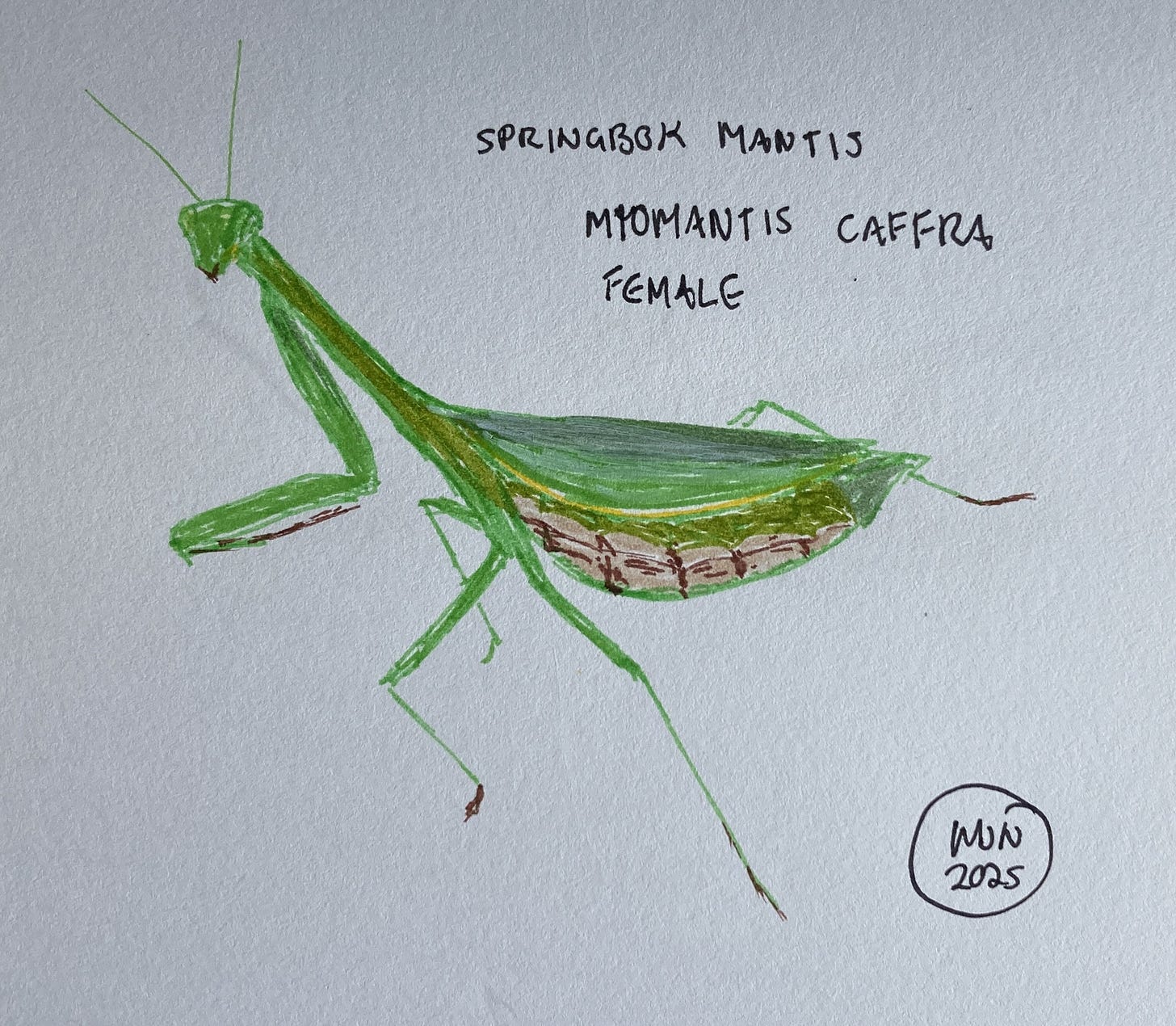

By the time I was in my last years at school, something had changed. I began finding very strange praying mantises in the garden. None of them were the bright green of the praying mantis I knew – some were pale green, some a dull yellow and some were almost blue-green. Their shape was different too. The area of the body just behind the head was a completely different shape, narrow like skinny neck instead of broad and flat. The males were skittish and flew away at the slightest disturbance. The females had shortened wings and didn’t fly at all.

Somehow – I have no idea how since this was pre-internet – I found out that they were a newly-arrived South African species which is commonly called the Springbok mantis. I was intrigued and began noting all the different variations in colour. I kept a couple of them in a converted aquarium and fed them on leafhoppers. I loved to sit and watch them as much as I loved watching the New Zealand praying mantis, until I realised that I hadn’t seen the native species for some time. What had happened?

I remember wondering at the time whether the Springbok mantis was affecting the native species, which I’ll refer to here by its Māori name of rō. Perhaps the Springbok mantis was more aggressive and attacked the rō. Perhaps it was better at catching food, so it competed with rō and pushed it out that way. I also remember someone, although I don’t remember who it was, suggesting that the Springbok mantis may have brought with it a mantis parasite of some sort, and that this could be affecting rō. This made me realise some of the difficulties in understanding the interactions between species – even ones as distinctive and easy to observe as praying mantises. Was the Springbok mantis really affecting the rō and, if so, why?

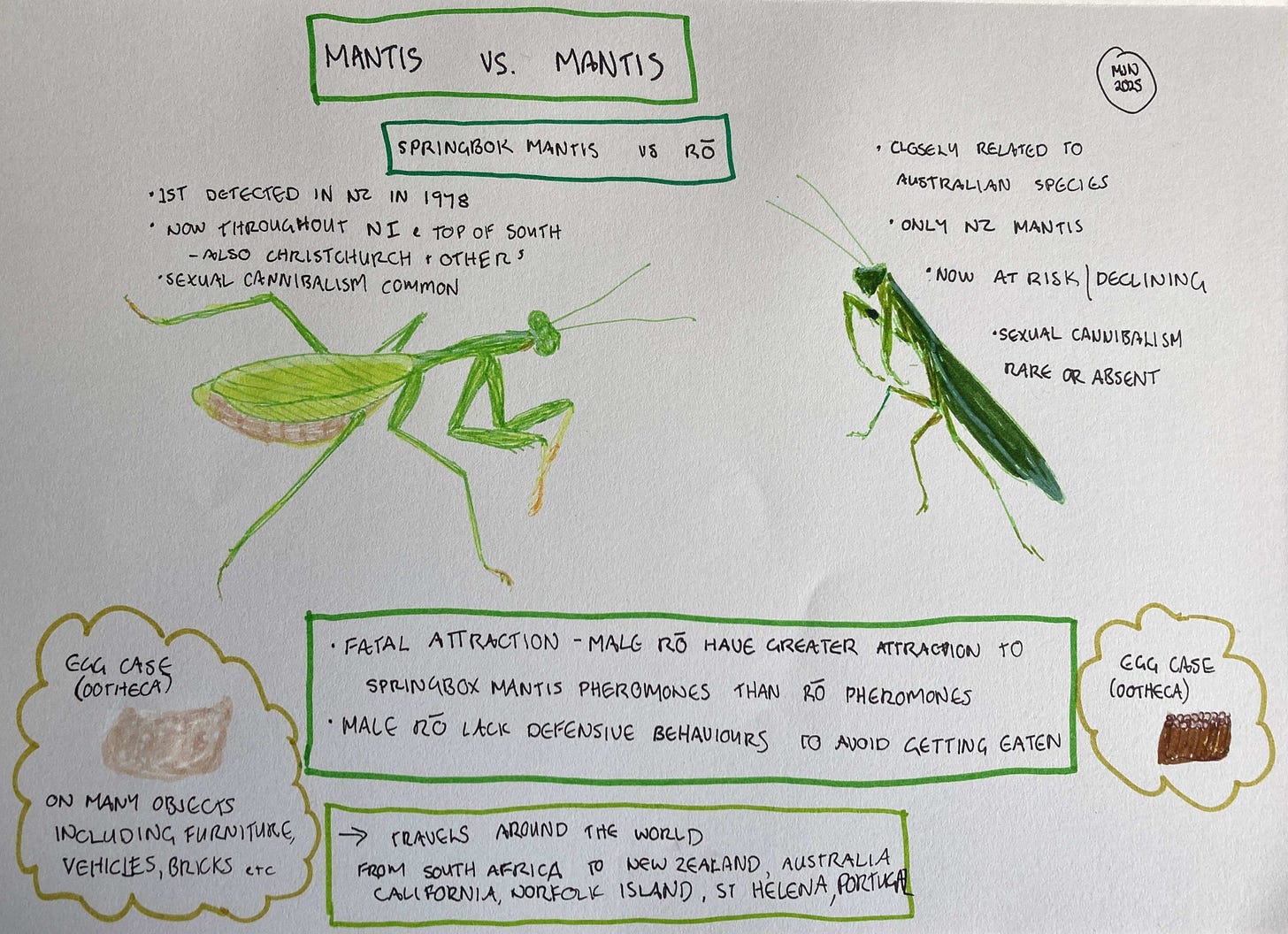

The Springbok mantis was first noticed in New Zealand in 1978. The initial detection was not made by a scientist, but by a schoolboy who spotted them in his garden. With a conspicuous species like a praying mantis, the public are great observers. The initial publication about the discovery noted that the new mantis was well-established and gradually increasing its range, but was not a pest species.

By 1990, the Springbok mantis was widespread in Auckland and it had also been found in a few places in Northland and the northern Waikato. There were observations that it was already more common than rō in some areas. The egg cases held more eggs, they hatched over a longer period of time and adults were better able to survive the winter. It wasn’t certain, but there were indications that the Springbok mantis might be replacing rō.

Although the Springbok mantis and rō were reported to have slightly different preferences for the kinds of plants they live on, they interact directly in two ways. Firstly, both species are voracious predators of all kinds of insects, including other mantises. As well as eating their own kind, the Springbok mantis preys on rō. However, while rō will eat each other, there are very few observations of them eating the Springbok mantis.

The second interaction is more surprising. Male rō seemed to have trouble distinguishing female rō from female Springbok mantises, and will mate with either. In fact, they prefer the attractant chemicals released by female Springbok mantis to those produced by their own species. This is more than simply a waste of effort. All too frequently, it is deadly.

The praying mantis is known in the popular imagination for two contradictory traits. The first is the way they hold their front legs, which makes them appear to be praying and gives them their name. The second is their unholy habit of sexual cannibalism, where the female kills and eats the male during or after mating. Not all species do this, at least not to the same extent. Sexual cannibalism is rare among the rō. On the other hand, the Springbok mantis has a high rate of sexual cannibalism, with one study showing that more than 60% of mating attempts led to the male being eaten before he was able to mate. Other studies have shown lower rates, but still high, around 40%, well above the average for praying mantises.

In an attempt to avoid being eaten, males of the Springbok mantis either approach cautiously or fight back. But what about the rō? They are not adapted to highly predatory females and lack the behaviours which provide some protection to male Springbok mantises. Well over half of encounters between Springbok mantis females and male rō were fatal for the male.

These findings provide a plausible mechanism for the Springbok mantis reducing the number of rō, but is this really happening? This is difficult to know for sure. Many papers refer to a decline or apparent decline in rō, but I haven’t seen any which provide more than anecdote. I spent some time looking for evidence, and there may be something I’ve missed, but it doesn’t look as if much has been published.

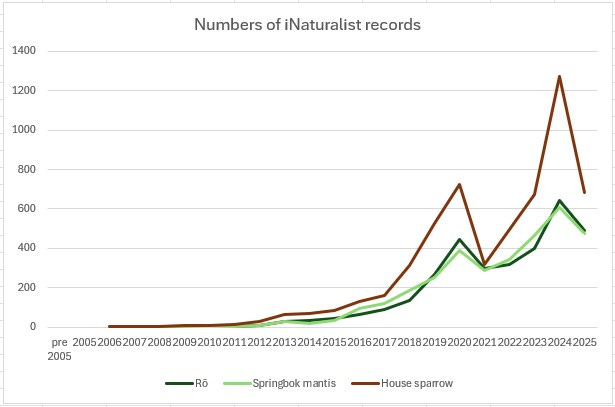

I decided to see what citizen science could tell me, so I looked at the records on iNaturalist. Since the Springbok mantis and rō are the only two praying mantises in New Zealand, and they are easy to identify and photograph, I thought they’d be the kind of species which people would report. Sure enough, both Springbok mantis and rō are among the most frequently reports insects. There are more than 3,000 records of each. However, while there is some useful information on iNaturalist, the records also show why field studies need to be carefully designed if we want them to give us accurate information about species numbers.

What iNaturalist reliably tells us is that rō is still a widespread species. Over the last two years, there are records from one end of the country to the other, with the only obvious absence on the South Island’s West Coast, where it hasn’t ever been reported, as far as I can tell. Springbok mantis is now found throughout the North Island and is widespread in the Nelson and Marlborough regions in the South Island. There are also records from in and around Christchurch and a few from Kaikōura, Dunedin and the West Coast.

iNaturalist gives a good indication of the distribution, but the numbers aren’t so helpful. Both mantis species show a steady increase from 2005 until 2019, with numbers fluctuating from then on. This tells us nothing about what’s happening with mantis numbers though. It simply reflects what is happening on iNaturalist as a whole. I compared the records of the common house sparrow, which the New Zealand Garden Bird Survey indicates has held steady since 2014 except for a slight decline in the last 2 years. Sure enough, the pattern is exactly the same as for the mantises. I even made a graph to show how closely the patterns match.

Although iNaturalist can’t tell us long-term trends, a close look at Auckland’s North Shore, where I grew up, is more informative. My childhood memories suggest that rō was a common species prior to 1980, one which I encountered often in the garden and which was familiar to many people I knew. The Springbok mantis has now been there for around 40 years. When I looked at iNaturalist records for the last two years, I was reassured to see that rō is still present, so my perception of it vanishing wasn’t entirely correct. However, there were only 9 records of rō, while over the same time period and area there were 90 records of the Springbok mantis. It’s also likely that these figures overstate the numbers of rō compared to Springbok mantis, since there’s evidence that rarer species are over-represented compared to common species on iNaturalist.

If we look at Wellington, where the first record on iNaturalist dates back to 20161, the picture is different. There are almost double the number of records for rō compared to Springbok mantis over the last two years. The Kāpiti coast is an outlier, though. There, the first record of Springbok mantis was in 2017, but records of it now well outnumber those for rō, although not to the same extent as in Auckland.

Why isn’t there more reliable information? In short, it’s not easy to get. Unless a species is extremely rare and confined to a limited area, it’s impossible to count them all. Instead, we need to rely on a sample, for example, by setting up plots of a certain size and counting all the praying mantises found. The reliability of sampling varies depending on a wide range of factors, including the study design and the skill of the observer. Then, the sampling needs to be repeated over time to show whether there is a trend. Many animals and even some plants show large natural fluctuations in their numbers, making it difficult to detect real trends. How long it takes depends on the design of the study and the size of the trend, but for most animals it takes at least 10 years. Using different observers over the course of a study can increase the time it takes to get reliable results, too.

Although there may not be published papers, there is enough concern among experts that rō was classified as an at risk and declining species in 2012, under the official classification for threatened species in New Zealand. But putting it on a list doesn’t change what’s happening. It’s just one more species under pressure from the way we’ve transformed New Zealand with new plants, animals and microbes from around the world. At this stage, as far as I can tell, we are simply hoping that rō survives.

Since arriving in New Zealand, the Springbok mantis has continued its travels. In Australia, it is now well-established in parts of Victoria, New South Wales and Norfolk Island, with a few records from Adelaide, Brisbane and Perth. In California, it’s established in San Diego and Los Angeles, with records from in and around San Francisco. It has a foothold in Europe, too, with reports from Lisbon in Portugal. It’s even found its way to St Helena Island in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

How has it managed this? And how did it get to New Zealand in the first place? Different sources offer a range of views, including the pet trade or on live plants, either as egg cases or juvenile insects. While the pet trade may explain countries which are more tolerant of exotic insects as pets, it’s unlikely to be the case for Australian and New Zealand. It’s possible they arrived on live plant material, but I have to agree with those who suggest egg cases on objects are more likely than live plants. Firstly, live plant material is subject to much closer scrutiny than what is sometimes called inanimate cargo, such as vehicles, containers and furniture. Secondly, there are numerous records of the Springbok mantis laying egg cases on these types of inanimate object, on iNaturalist and in publications. Egg cases of other kinds of praying mantis have been detected on used cars arriving in New Zealand as well.

In fact, the Springbok mantis is a perfect example of the kind of pest I used to work on in biosecurity. Sometimes termed hitchhikers or contaminating pests, these are species which don’t have a strict biological association with the material they are transported on. On a consignment of oranges, we could expect to find known citrus pests and diseases, and we can figure out what those are from a body of literature on the subject. We can’t do the same for used cars.

Whether a car, or a container or a set of garden furniture arriving at New Zealand’s border carries a hitchhiker pest depends on where it was used or stored before it was sent here. Since this is almost impossible to know by looking at it, or even from the paperwork which accompanies it, hitchhiker pests are often regarded as “random”. But they are not. Certain types of insect2 have a propensity for international travel, because they have a life stage which requires no food, can survive adverse conditions stage and which can end up on a wide range of substrates. For the Springbok mantis, this life stage is the egg case, but for other species it can be another life stage.

All it takes is for an object to be in the wrong place at the wrong time and it will pick up insect hitchhikers.

The Springbok mantis, then, is part of a bigger picture. It’s not an isolated curiosity, nor is the decline of rō a singular tragedy. Every plane and ship to reach our shores, every vehicle or sea container we import, every imported product we buy, as well as everything we send overseas, is part of a giant global experiment. There has been a huge amount of work in New Zealand, and a few other countries, to try and prevent unintended new species of this kind coming in. Ultimately, though, the volume of trade means that we simply can’t stop everything.

It’s not clear whether Springbok mantis was present in Wellington much before this. A 2011 thesis states that it is widespread in the North Island, but this is referenced to a personal communication. The 2016 Wellington record contains a comment from an experienced naturalist that this was the first they had heard of the species in Wellington.

Some other groups, such as certain spiders, snails, lizards and others, also have a propensity for travel, but usually for slightly different reasons.

Really interesting thank you! I only found out about the Springbok mantis last year, after seeing an egg case at my sister's place on the Shore. Quite different from the rō version. (Which I definitely saw around the Shore growing up, but never knew they were mantis eggs.)

Thanks Melanie. I have been vaguely concerned about this for several years but never really looked into it properly. Your great article has unfortunately confirmed my fears. Maybe we could all dye our ears blue in solidarity for the blue-eared native mantis? Meanwhile, hopefully natural selection is working on a fix, which must be (as is the case in all serious problems today) the need for smarter males!