I have something a little different for you this week. During May, I took part in an online challenge on the social media platform Bluesky. I’ve been enjoying this platform because there are lots of scientists, science communicators and writers there, and I’ve been able to follow their work. I’ve also been enjoying the work of artists doing science-themed art. One issued a challenge called Moth May, where the aim was to draw a moth every day. She even had a list of suggested moths to draw.

When it comes to drawing, moths are relatively easy. Their shapes are usually simple and when they are resting they aren’t as 3-dimensional as many other animals. Some years ago, I was assessing the risks of various moth species to New Zealand, and I developed the habit of doodling moths in the margins of my meeting notes. I decided to give the challenge a go.

I printed out the list of moths, then searched for photos of them on iNaturalist. Because the Moth May challenge originated in England, most of the moths on the list were European. However, I substituted a few of the European species for moths which are present in New Zealand.

Did I manage to draw a moth every day? No, but I managed 23. Was I happy with my drawings? Somewhat – I was pleased with some and not with others. I might have been too intimidated to share my drawings if I compared them with those done by the other challenge participants, but I mostly managed to avoid doing so.

Drawing depends to some degree on natural ability, just as writing does, but it’s still more of a skill than a talent. While talents are innate, skills improve with practice. So, I sat down and spent a little time drawing moths every day. It was fun, and it gave my brain something other than words to focus on. My ability to accurately draw what I see might have improved a little, but my observation skills have certainly improved much more. I really notice moths now. It’s given me a deeper understanding and appreciation for another aspect of the natural world.

The diversity of moths is astonishing. While it is true that many are coloured a nondescript brown, others are as showy as any butterfly. Their wings are often textured to better camouflage them against their preferred place to rest. Others are mimics. I drew one moth which resembled a mosquito and another which resembled a fly. I’ve also learned some intriguing moth facts. From their camouflage abilities to their efforts in controlling invasive weeds, there’s much to admire and appreciate about moths.

So, here are some of the moths I drew, and some of the things I learned. Over the next few months, I will share more of my moth drawings and what I’ve learned.

Peppered moth

I first heard of the peppered moth at school, when my class was learning about evolution. Prior to the industrial revolution in Britain, this moth was predominantly white speckled with black. But in the 19th century, black forms, or those which were intermediate between black and the usual form, began to predominate. The increase in black forms coincided with industrial pollution such as soot from coal, which darkened surfaces.

Biologists noticed this change, and it helped them to understand evolution better. Light coloured moths were not as effectively camouflaged and became vulnerable to predators, while more of the better camouflaged black moths survived and therefore came to dominate. As pollution was reduced in the second half of the 20th century, the black forms declined and more typical forms returned.

Biologists are still studying this moth, because the picture is a little more complex than I’ve summarised here. Nonetheless, it’s a powerful reminder of both the impact we have on the environment and also the ability of nature to adapt and survive.

Mint moth

This lovely little moth demonstrated the hazards of drawing wildlife from photos on iNaturalist without ever having seen them in person. Everyone else in the challenge drew this moth much more of a reddish-purple. I looked through more photos, and at certain angles the colour did show, but the photo I drew my moth from just looked red-brown.

The mint moth is one of the species which reminds us that insects are good taxonomists. It feeds on plants which include mint, catnip, marjoram, thyme and lemon balm. All the plants it feeds on belong to one botanical family, the mint family. I’m always intrigued to discover other living things which recognise the same categories in plants as we do. Another intriguing example is the myrtle rust fungus, which infects only members of the myrtle family.

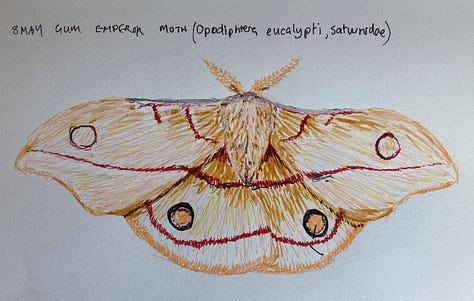

Gum emperor moth

One of the entomological highlights of my childhood was finding a caterpillar of the gum emperor moth. It was the biggest caterpillar I’d ever seen, a distinctive blue-green and adorned with orange and blue spikes. As its name suggests, it mainly feeds on gum trees, which means it’s not a New Zealand native. It arrived from Australia some time before 1915 and found we had planted lots of Australian gum trees. So, it made itself at home.

It can be damaging to gum trees, so I suppose it would be considered a pest by those cultivating gum trees for timber. It does feed on a few other types of trees too, including some fruit trees. My delight in this species must therefore be tempered with the recognition that it can cause problems. Nonetheless, it remains one of my favourite moths.

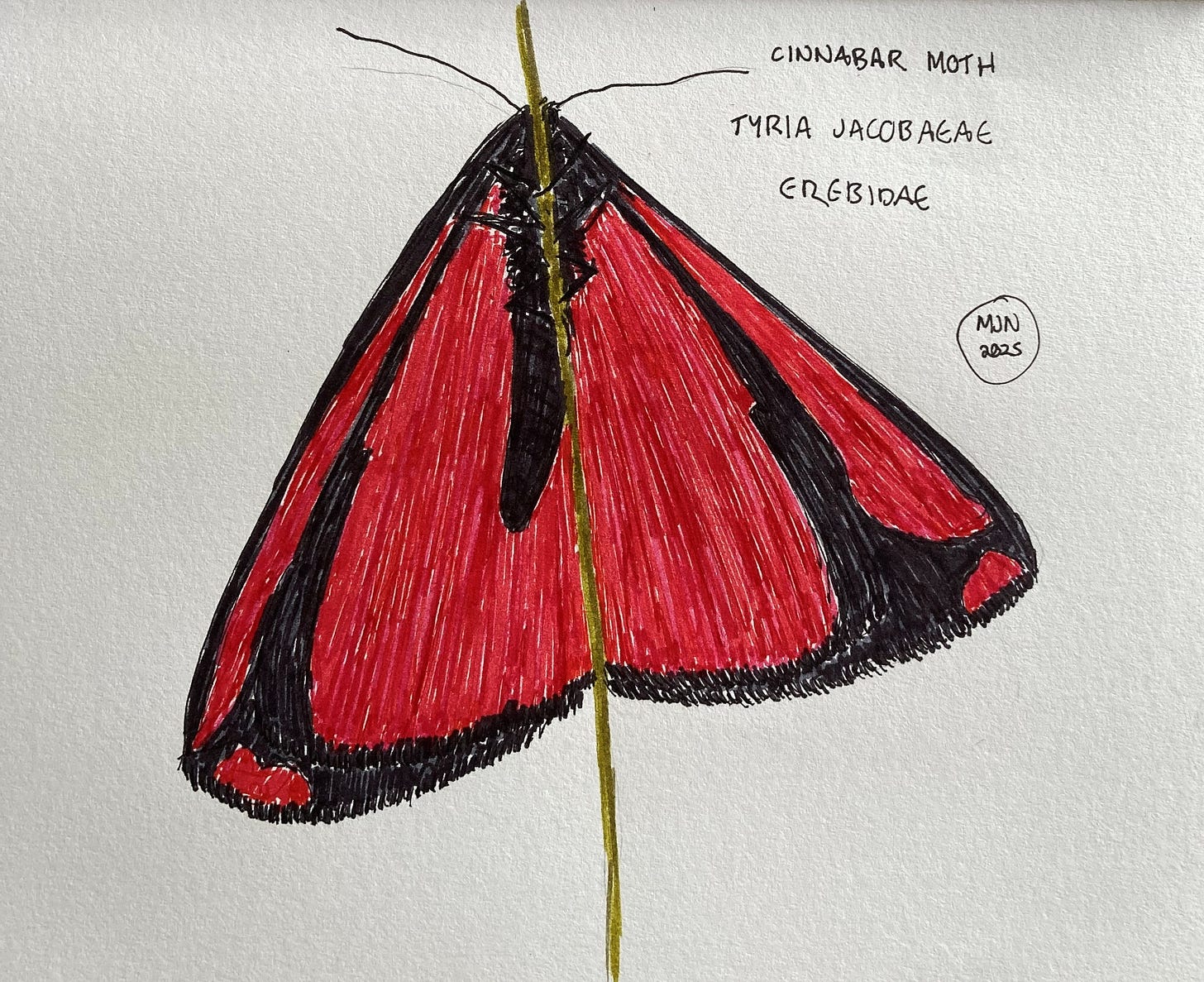

Cinnabar moth

The cinnabar moth was part of the official Moth May challenge, as it’s a European species, but it is also in New Zealand. Unlike the gum emperor moth, though, it was a deliberate introduction. It feeds almost exclusively on ragwort plants, and since ragwort is a serious weed in New Zealand pasture, it was introduced as a ragwort control measure. While it can be damaging on individual plants, it hasn’t had much impact on the overall ragwort population. There’s another moth which has had more of an impact in some areas, but it’s less colourful. A third moth was introduced but failed to establish. However, the biocontrol agent with the most impact on ragwort has been the ragwort flea beetle.

I might try drawing some of the other biocontrol agents at some stage, but I do love the colours of the cinnabar moth.

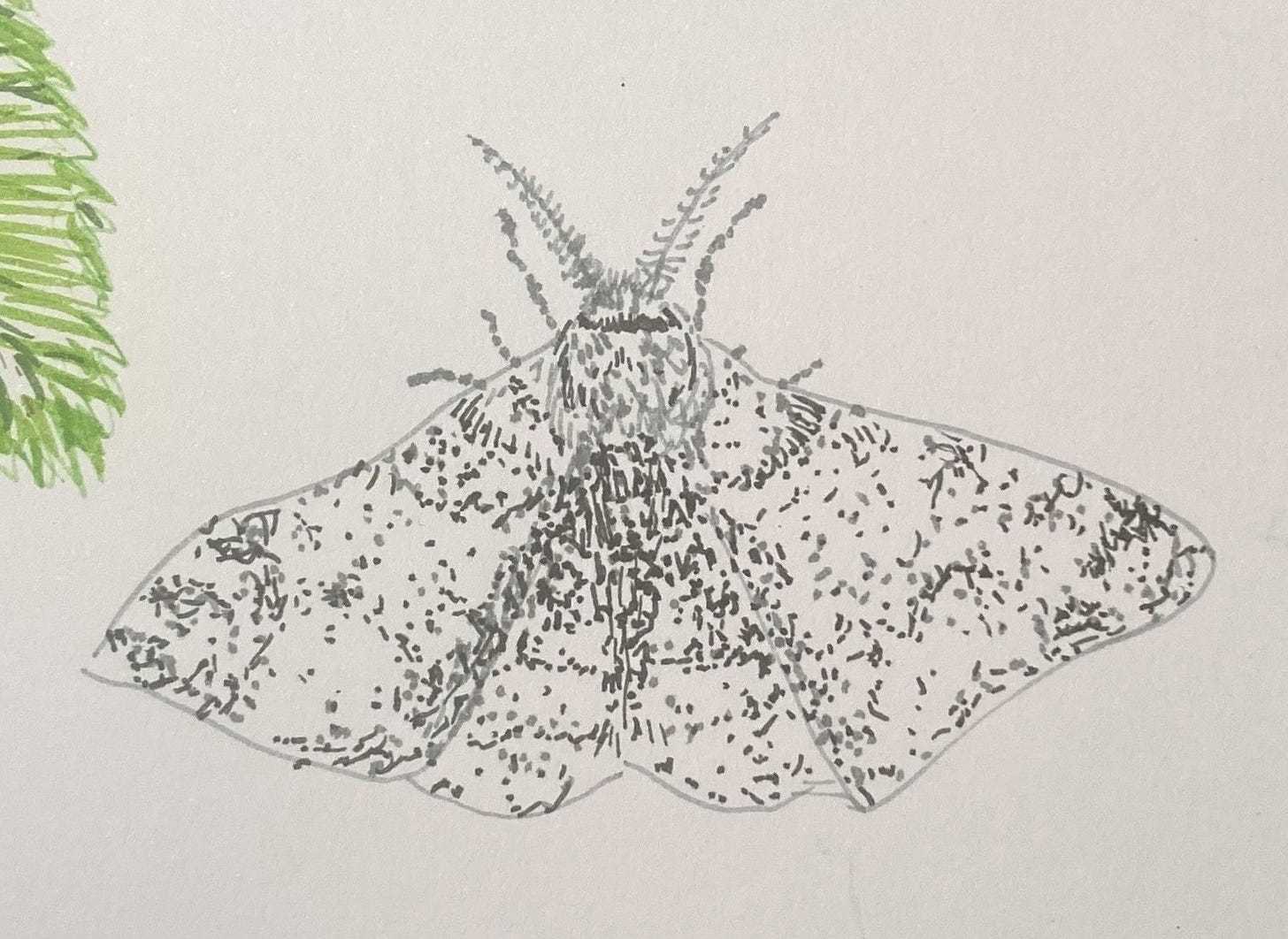

Green carpet owlet moth

Finally, here’s one of the many New Zealand moths which stand in marked contrast to the peppered moth. Like the peppered moth, these are camouflaged on tree trunks. However, since the trunks and branches of trees in the New Zealand forest are usually festooned with mosses, lichens and liverworts, they have a very different kind of camouflage. Until I began the Moth May challenge, I had no idea how many New Zealand moths were green, so that they are camouflaged against mossy tree trunks.

I haven’t come close to doing the beauty justice. It isn’t only the colours of this moth which perfectly mimic the mosses it sits on. When viewed closely, the textures are extraordinary. Here is a link to the iNaturalist page, if you want to see photographs.

Ichneutica plena · iNaturalist

If you would like to see some of the other moth artwork from Moth May, here’s a link to the challenge on Bluesky1. There’s some lovely artwork there, including moths made of felt.

I’m not sure if this link works for people who don’t have Bluesky accounts.

I love moths too and remember night windows covered it’s them, when I was young. My favourite is the cabbage tree moth, Epiphryne verriculata, which I found on te kouka one night, when nothing with William Brocklesby. He is planning another night moth monitoring in spring. I’ll keep you posted.

I can be overrun with moth caterpillars in my garden. I have a buckwheat and a ceanothus that are trying their best to recover from the moths that feasted on them last year. We get hummingbird moths from time to time. They can be delightful. https://youtu.be/S0qm_L_HPdM?si=ZraMkohy6ue5NdbW