When the sun sets on Takapourewa, it takes the island back in time. During the day, when I’d walked around the more accessible area looking at invasive weeds, it was clear that the island had been extensively altered by human activities. In the early 1890s, when the island at the outer edge of the Marlborough Sounds was more commonly known as Stephens Island, a lighthouse had been built there. Forest was cleared to allow the lighthouse keeper to farm livestock for food. By the time I visited, in the early 2000s, the forest was regenerating, but I could still see the effects of the past clearance.

At night, though, none of that is obvious. During the breeding season, the island’s seabirds, such as the tītī wainui or fairy prion, return to their burrows. Their chattering and cackling brings the island alive. Colonies of seabirds just like those on Takapourewa were once present throughout New Zealand, even some distance inland. Takapourewa shows me what the mainland of New Zealand was once like, before the introduction of mammal predators.

But there’s something else on the island, something which emerges from seabird burrows at night and takes the island even further back in time. It’s the tuatara, a reptile so ancient that there’s nothing else close to it still living. Takapourewa is one of the few places it’s survived in the wild.

You can be forgiven for thinking that the tuatara is a kind of lizard – the first European biologists to see it believed that it was. But by the late nineteen century, they began to realise that it was something different. The reptiles are divided into three main groups, the turtles, the crocodiles, and the lizards and snakes. But the tuatara belongs to none of these. It has more resemblance to fossils than any living reptile.

In fact, the tuatara belongs to a group of reptiles so ancient that they have survived not one but two mass extinction events. At the end of the Cretaceous era, 65 million years ago, a meteor strike wiped out almost all the dinosaurs, apart from those which became our modern birds. The tuatara’s ancestors survived too. But they also survived a mass extinction 200 million years ago, which preceeded the rise of the dinosaurs. Once, the tuatara had numerous relatives. Now, it is all that remains of its ancient lineage, as it clings to survival on a few islands free from rats and other mammal predators.

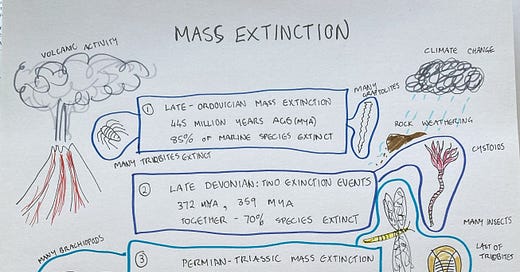

Since life first emerged, at least 3.5 billion years ago, but possibly hundreds of millions of years earlier, there have been five mass extinction events. Strictly speaking, I should say that there are five that we know about, since before the first of these documented events 440 million years ago, the Earth had already undergone some massive fluctuations in its atmosphere and climate. For example, 2.5-2.2 billion years ago, bacteria evolved which used a new chemical process for producing food from sunlight, producing oxygen as a waste product. Today, almost all life depends on this chemical process, called photosynthesis, but at the time it was a catastrophe. For most of the microbes alive at the time, oxygen was toxic. It’s likely that the buildup of oxygen in the atmosphere from photosynthesis caused many microbes to become extinct, but since microbes don’t make good fossils, we can’t be sure.

Extinction is a normal part of the evolutionary process, and the species which exist today are only a tiny proportion of the species which have ever existed. However, extinction has never been a constant process, where species die out at regular intervals. There are fluctuations in both the rate that species die out, and the rate at which new species evolve. The Earth has had long periods with few extinctions, and shorter periods with many extinctions.

The five periods defined as mass extinctions were notable not only because large numbers of species became extinct in a relatively short time, but also because many different types of species became extinct. There are different definitions of mass extinction, but the percentage of species which became extinct in the five defined periods are estimated to range from 60% to 96%. The time period over which the species became extinct would seem relatively short only to a geologist – typically under two million years.

The mass extinction which saw the end of the dinosaurs is the most well-understood mass extinction. Although triggered by a massive meteor striking the Yucutan Peninsula in Mexico, the subsequent extinction of 75% of the world’s species took place over hundreds of thousands, perhaps up to 2.75 million, years.

Other mass extinctions are less well-understood. The mass extinction 200 million years ago is thought to have resulted from a period of widespread volcanic activity, which released carbon dioxide, triggering a rise in global temperatures. Exactly why temperatures rose is debated. It may have been caused by the carbon dioxide alone. However, it’s also possible that a small rise in temperature caused by the carbon dioxide triggered the release of methane which had been trapped in undersea ice and permafrost, leading to a much larger rise in temperature. The mass extinction before that one, 251 million years ago, was the largest known, with the loss of 90-96% of species. It has been linked to a number of factors, including increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and a lack of oxygen in the ocean. Before that, the two earlier mass extinctions have been attributed to a range of causes – meteor strikes, nutrient runoff from land to sea, a lack of oxygen in the oceans, weathering of rocks and a decrease of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Scientists have suggested that a sixth mass extinction, caused by humans, may now be underway. Is this true? How do extinctions caused by humans compare with the mass extinctions of the distant past?

We know far more about modern extinctions than we do about extinctions in the past, but even today we aren’t sure how many species have become extinct, or are at risk, as a result of human activities. Firstly, we aren’t sure when humans first began causing extinctions. Over the last 130,000 years, very large mammals have become extinct in many areas, even though a similar rate of extinction hasn’t been seen in smaller animals. More than 80% of mammals larger than 1000 kg, and more than 50 % of mammals larger than 100 kg have become extinct during this time. In North America and Australia, these extinctions appear to have happened in the years after humans arrived, while in Africa, where very large mammals evolved alongside humans, most have survived. However, there is also evidence that climate change related to the end of the last ice age may have been the cause, affecting temperate areas more than tropical. Scientists have debated, and continue to debate, whether the extinctions are caused by climate changes or human activity.

Even if we look at only the last few hundred years, it’s still difficult to count extinctions, because many species remain undiscovered1. New species are constantly being described, even birds, mammals, trees and showy orchids, among the more conspicuous life forms on the planet. While the discoveries result partly from scientists revising their definitions of different species, they still show that our knowledge is limited.

When it comes to less conspicuous forms of life, we know even less. Scientists have estimated that only 5% of mammals, or around 300 species, remain undiscovered. For insects, they’ve estimated that 80%, more than 4 million species, are undiscovered, or at least haven’t been named and described. There is still considerable debate on how many species there are – the most widely quoted estimate is 8.7 million, from a paper published in 2011. Recent advances in our ability to identify species from their genes suggest that this number greatly underestimates the true diversity.

If we don’t know how many species exist now, how can we know what we’ve lost in the last few hundred years? The short answer is, we can’t. But we can look at what we do know, and then estimate from that.

For birds, mammals and amphibians, 285 are known to have become extinct since the year 1500, around 2% of named species. Even for these groups, which are well-studied, the actual extinctions are likely to be considerably higher, perhaps almost double in some cases. And 500 years is a very short time compared to the time periods for past mass extinctions. Scientists have attempted to compare the recent rates of extinction with the usual rate outside periods of mass extinctions. They’ve suggested that the current extinction rate is 100 times greater than it would have been without human activities.

When it comes to insects, only 59 species are recorded as extinct on the official list from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. This works out at only 0.001% of species, which might suggest there’s not much of a problem. However, fewer than 13,000 species have been assessed, out of the million which have been named. There are far fewer estimates of actual extinctions – one estimate based on the extinction rates of British insects was used to estimate that 7000-14000 insect species may have become extinct. British insects were used simply because they have been well-studied, and it’s a bold claim to suggest they are truly representative of the global situation. Another study looked at extinctions of land molluscs – slugs and snails – and estimated that 10-17% of a total of 30,000 species may now be extinct. One estimate suggests that 250,000-500,000 species of insect may have become extinct in recent times.

New Zealand is certainly not typical, but it does paint an interesting picture. Because humans have been living here for such a short time, less than 1000 years, we can get a better understanding of the total number of species which have become extinct due to human activities. Around 75 species are known to be extinct, but that figure is biased towards birds, which leave bony skeletons to be examined by scientists long after they are gone. The article in Te Ara, New Zealand’s online encyclopedia, lists numbers for extinctions of birds, frogs, lizards, fish and plants, then simply refers to uncounted losses of invertebrates (insects and other animals without backbones). We just don’t know.

What we do know about New Zealand extinctions is frightening, though. In less than 1000 years, around half of our land vertebrates – 59 birds, 3 reptiles, 2 frogs and one bat – have disappeared. For this group, the percentage figure is nudging up towards the past mass extinctions, and in a very short time.

But extinctions aren’t stopping. While desperate efforts in New Zealand have brought some species back from the brink, if we stop we could easily lose many species. We currently have more than 3700 species at risk, and the highest proportion of threatened native species for any country in the world.

Globally, estimates vary for how many species are under threat right now. The official list has more than 6000 species classed as critically endangered – the highest category of threat. Over the last 40 years, more than 150 birds have been moved from the category of least concern, which means they aren’t considered threatened, and onto the list of species which are at risk. Dozens more have moved from lower to higher threat categories.

The official classification is only one way to look at the problem. Estimates which take unassessed and unnamed species into account give much higher figures. A US study from 2005 found that there are more than ten times the number of endangered species than the official lists suggested. In addition, many species around the world are suffering massive declines in their total numbers and their range, even if they aren’t likely to become extinct in the immediate future.

What’s staggering is not so much the numbers, it’s the rate of extinction. A 2015 study, using just the official list, found that the rate of vertebrate extinctions was 24-85 times faster than the mass extinction which saw the demise of the dinosaurs. If extinctions continue at this rate, then we will indeed achieve the dubious distinction of causing the 6th mass extinction.

I’m sorry, this is a depressing place to finish an article. Things are dire, and the absolutely horrible situation in the US is making optimism difficult. What keeps me going is looking at the things people are doing to make the world better. Seeing the recovery of native plants at my local forest reserve brings me joy.

I realise that all around Wellington, environmental heroes are taking steps to make our city, and our planet, a better place. So, in a couple of months I’m going to take a closer look at what is going on. I’ll be bringing you a series of articles filled with people who are quietly making a difference – and I’m hoping to put Substack’s new live video feature to good use too. I can’t wait to bring you some good news!

That is, undiscovered by scientists – they are often known to indigenous people.

Liking though is not really the right response 🤷 - very clearly written though

Great post and still enjoying your illustrations. I recently read Elizabeth Kolbert's book "The Sixth Extinction". I learned a lot and it included great discussions on how we estimate current species and specie loss.