A sour taste

The strange story of a medical breakthrough discovered and then lost, again and again (12 minute read)

As I was drawing one of New Zealand’s most endangered plants for last week’s article, I was reminded of a strange story. At first glance, it appears to be an obscure piece of historical trivia, a footnote to important events but not important in itself. But it’s more than that. I’ve realised that it illustrates a risk to our health which should be improbable but which we shouldn’t ignore right now.

The plant I was drawing was nau, a relative of cabbage which was gathered and eaten by Captain Cook and his crew when they visited New Zealand. It reminded me of Cook’s role in managing the scourge of seafarers, scurvy. On his voyages, Cook was remarkably successful in preventing scurvy among his crew. In an era when voyages of similar length sometimes lost half of their men to scurvy, Cook lost none on his own ships and only one on the ships accompanying his1.

For a century, scurvy appeared to be a disease in decline. Then, it re-emerged among explorers attempting to reach the North and South Poles. The reason seems obvious – fresh fruit and vegetables aren’t available on the Arctic sea ice or in Antarctica. But that was only a part of the reason. In fact, there was a way to prevent and treat scurvy under polar conditions, and a few explorers, notably Roald Amundsen, knew it. Most of the explorers, though, were following advice about scurvy which was fundamentally incorrect. This once-preventable disease didn’t return as a killer because there was no preventative or treatment available. It returned because the preventatives and treatments which worked were rejected or dismissed because they didn’t fit the prevailing theory of the disease.

Today, we are facing the resurgence of diseases such as measles because vaccines are being rejected. The reasons for this are complex, and are not a direct parallel with scurvy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Nonetheless, the story of scurvy illustrates some important insights into the advancement, and occasional regression, of science and medicine.

We now understand that scurvy is a disease caused by a lack of vitamin C, also known as ascorbic acid. It’s necessary for a number of processes in the body, such as making collagen, a structural protein which is an essential part of many tissues. Humans and other primates are unable to make vitamin C, and so need to obtain it from the diet. We also can’t store it in our bodies – if we eat more than we need it’s simply excreted. It takes 4-12 weeks of insufficient vitamin C for scurvy to develop.

Some of the most dramatic and frightening symptoms of scurvy result from the loss of collagen. The skin and blood vessels are weakened, leading to bruising and bleeding. The gums bleed and teeth become loose, eventually falling out. Joints ache and swell, especially the knees. Even hair growth is affected, with hairs developing characteristic distortions. Untreated, or without access to vitamin C in the diet, scurvy leads to organ failure and death.

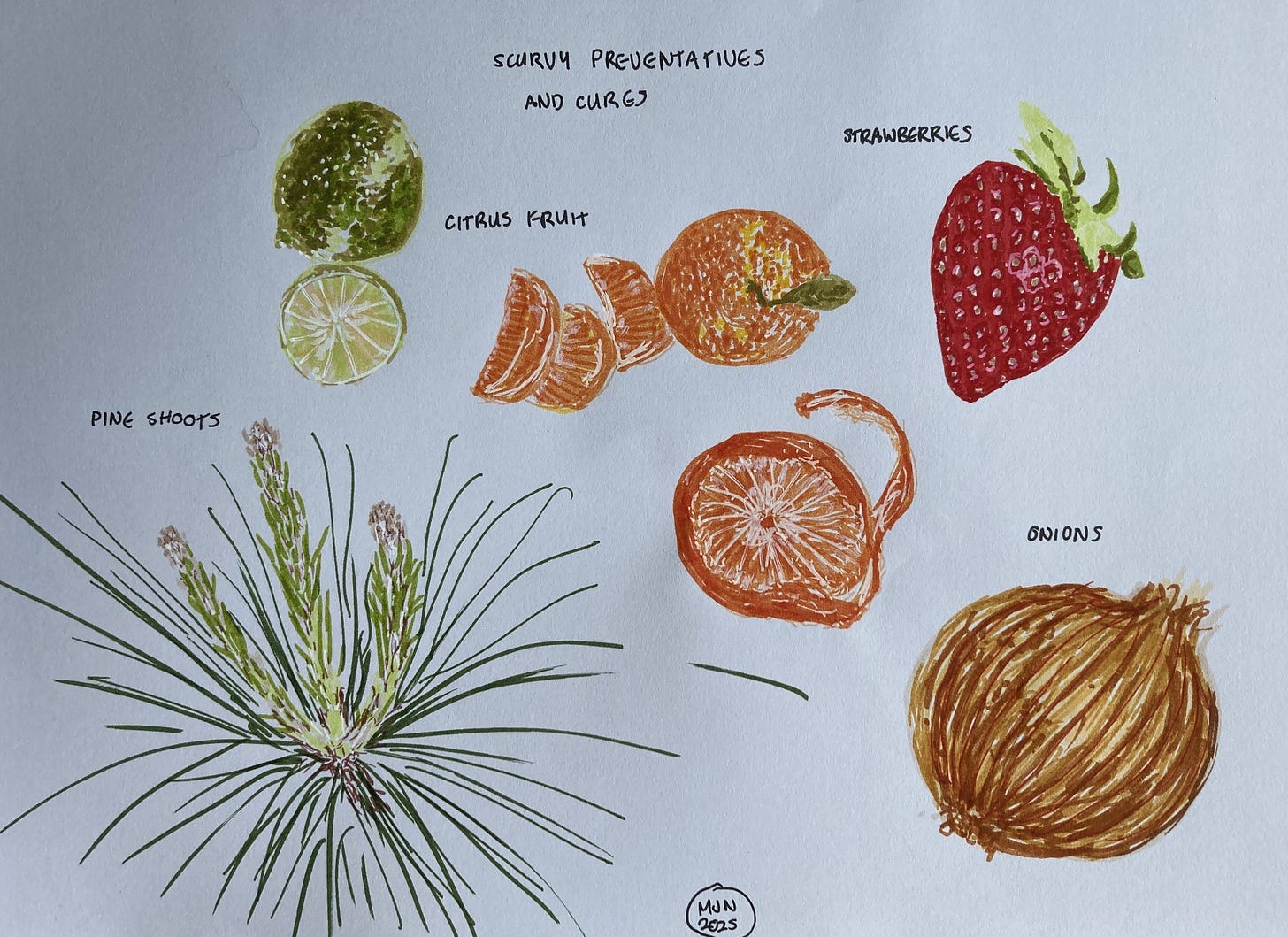

Most of us associate vitamin C with citrus fruit, but it’s present at varying levels in a wide range of foods. Strawberries and kiwifruit have as much as, if not more than, citrus, as do some vegetables, including broccoli. Even fruits and vegetables with less than citrus still have considerable amounts. What’s less well-known is that there’s vitamin C in fresh meat. The levels are lower than in plants, but some organs, notably the liver and adrenal glands, do have a reasonable amount. It’s particularly high in seal liver and whale skin, traditional food of the Inuit, who survived on a diet with almost no fruit or vegetables.

Although it’s present in many foods, vitamin C is easily degraded, particularly by heat, but also by exposure to air and almost any storage method, including freezing. This doesn’t mean that cooked, frozen or dried foods have no vitamin C, but they have much less than they would fresh and raw.

Scholars have stated, with varying degrees of confidence, that scurvy was documented in ancient texts from Egypt, Rome, Greece, India and China. In at least some of these, there is evidence for some understanding of how to treat the disease. The Ebers papyrus for example, dating back 3500 years, suggested onions and other vegetables.

Pliny the Elder, writing around 2000 years ago, demonstrates some of the challenges our ancestors faced in untangling the causes and treatment of the disease. He describes an illness among the soldiers of the Roman general Germanicus, was the nephew of the emperor Tiberius and father of the emperor Caligula. The soldiers were stationed in a coastal area with limited access to water for several years. After about two years, they developed a disease which caused their teeth to fall out and their knee joints to become weak, a combination which strongly suggests scurvy, although there’s no mention of other symptoms. Fortunately, the local inhabitants knew of a cure, a plant known as britannica. The soldiers ate it and recovered.

According to Pliny, the disease was caused by drinking the water from the only available spring. Here we can see the first difficulty in understanding scurvy. The soldiers drank water from a particular spring for two years and became sick. This observation is what statisticians call a correlation. There are two factors, drinking from the spring and becoming ill, which appear to be correlated or linked. Such a link may be made by casual observation or by rigorous data collection and statistical analysis, but either way, there’s trap for the unwary.

Pliny, and presumably the soldiers, noted these two factors and assumed that one caused the other. However, statisticians have a saying: correlation does not imply causation. Philosophers have an expression for it as well, the questionable cause fallacy. Just because two factors show an apparent link, it doesn’t mean that one causes the other. There is, for example, a correlation between being admitted to hospital and dying within the next 12 months. In New Zealand in 2014, the year I happened to find data for, someone who has been admitted to hospital is 35 times more likely to die within the next year than the average for the population. Does this mean that going to hospital caused their death? Occasionally, something might have gone wrong in hospital, but mostly, no. Instead, there’s another factor, ill-health, which leads to both hospital admission and death.

There’s another type of correlation as well, one which is entertaining but meaningless. If you analyse a large number of unrelated factors, some will show a correlation simply as the result of chance. One website which collects these spurious correlations lists, among others, correlations between fire inspectors in Florida and solar power generation in Belize, between US margarine consumption and the divorce rate in Maine and, my personal favourite, the popularity of the name Sarah and remaining forest cover in the Amazon.

So, Germanicus’s soldiers faced three possibilities when they identified a link between drinking from the spring for two years and becoming ill. The first was that the drinking the water caused their illness. The second is that there was a link, but it wasn’t a causal link. Perhaps there was something else about that area which made them ill. The third was that the apparent link was entirely coincidental.

I’ve spent some time explaining this issue, because it’s fundamental to understanding what went wrong in our understanding of scurvy in the 19th century. It’s also something which remains a challenge in medicine today, particularly when attempting to identify risk factors for certain diseases (a topic I’ll get to someday).

In his description of the cure, Pliny demonstrates a different challenge with understanding scurvy. Germanicus’s soldiers were told to eat a plant named britannica, which they did, and were cured. Academics have debated what this plant was, but it actually doesn’t matter. We know now that vitamin C is found in numerous plants to a greater or lesser extent. There were probably numerous plants that they could have eaten which would have helped, but the locals had learned that britannica worked, so that’s what they used.

The idea that scurvy had a single remedy is one which appears again and again. In the 1500s, many of the men travelling with Jacques Cartier in the area which is now Quebec became ill with scurvy. Many died before local inhabitants recommended a tree called ameda. As with britannica, we aren’t sure what the plant actually was, but this isn’t particularly important. A number of different conifers native to the area would have worked, because many conifers contain considerable amounts of vitamin C in their needles. Soaking fresh pine shoots in beer was recognised as a treatment in Sweden. Men travelling with navigator and privateer Thomas Cavendish learned of a plant they called scurvy grass, actually a cousin of the brassicas. Oranges and lemons were also reported as a cure around this time. All of these cures, and more, were known, yet the disease remained a deadly scourge.

Among the most famous to propose a cure for scurvy is James Lind. He conducted what are often considered to be the first clinical trials. First, he read widely about the different proposed treatments. Then, he tested different treatments on men with scurvy and observed which proved most effective. Lind’s approach was important because it was an early step in overcoming the questionable cause fallacy. If a sailor with scurvy was given a treatment and then recovered, it might seem logical to conclude that the treatment was effective. But perhaps the sailor had been at sea for months and was now being treated on land, eating more fresh food. By giving the sailors different treatments and comparing them, he could be more confident that it was his treatment which made the difference, and not something else.

Lind showed that lemons were effective in curing scurvy, but from this point he went badly astray. To aid storage during long sea voyages, he proposed using a boiled lemon syrup. His error was to assume that scurvy was cured by some immutable property of lemons, so boiled syrup would work as well as fresh lemons. He then failed to test this assumption. If he had, he would have found the treatment ineffective, because boiling would have destroyed most of the vitamin C.

Captain Cook’s approach to scurvy was entirely different. He tried everything at once. He carried all the popular scurvy treatments of the time – Lind’s lemon syrup, portable soup (a meat broth cooked until it was so concentrated it was nearly solid), salep powder (a coffee substitute made from grinding the tubers of certain orchids), wort of malt (made from sprouted then dried cereal grains mashed with hot water) and sauerkraut. Of these, only the sauerkraut would have been any use. He recorded in his journal that the crew didn’t like it, but he convinced them to eat it by serving a large dish of it at the officer’s table and ensuring that all the officers ate it.

Also useful in preventing scurvy would have been the large quantity of onions he carried. These can be stored for long periods and have a considerable quantity of vitamin C. He also insisted on taking on fresh vegetables at every opportunity. If there were no vegetables, he and his men gathered wild plants and ate them. They even drank “spruce beer”, brewed from the leaves of various conifers and other trees.

This might sound dangerous in a place where the plants were unfamiliar, but with botanists on board to advise him, it isn’t as bad as it sounds. Although the species might have been unfamiliar, he and his crew were eating plants related to edible plants they knew from other places.

As a science experiment, Cook’s approach was useless. It would have been impossible to determine precisely what kept scurvy at bay on Cook’s voyages, because he was trying so many things. But for scurvy, it was exactly the right approach, especially the insistence on fresh vegetables of any kind. There were numerous valid treatments, and the best was whichever of these was to hand.

The appeal of a single solution, though, didn’t disappear. Alexander Addington demonstrated that lemon juice mixed with brandy and bottled with a layer of olive oil on top was effective. This became the standard preventative and treatment for the Royal Navy. In the mid-19th century, lemons were replaced with limes, lower in vitamin C but still of some value. However, the quality of the fruit varied, and treatment sometimes failed. And still nobody knew exactly what caused the disease, why the various treatments either prevented or cured it, and why they didn’t always work.

When scurvy broke out on an expedition to the Arctic in 1875, the debate on its cause was re-ignited. Had it been because they didn’t carry lime juice on sledging journeys in their effort to make their loads as light as possible? Was it due to the dark winters and lack of sunlight, or damp conditions below deck? Was it due to immoderate alcohol consumption, or simply the harsh conditions? The prevailing theory, though, was inspired by the recent discovery that microbes could cause disease. Scurvy, it was thought, was caused by a toxin called ptomaine, released by microbes in poorly preserved meat.

A few men, though, were not led astray by the latest theory and turned to a different solution. Among them was Frederick Cook, a doctor who spent time with the Inuit before joining a ship called the Belgica on an expedition to Antarctica. Before Scott and Shackleton, the Belgica expedition never landed on the continent, but they did spend a year stuck in sea ice and nearly died as a result. As the men sickened, Cook effectively took charge. Knowing that the Inuit never got scurvy despite a lack of fresh vegetables, he insisted that the men eat fresh seal and penguin. Among the crew, none took his advice to heart more than a young man called Roald Amundsen. When he became a hero for being the first to reach the South Pole more than a decade later, he credited Cook.

The ptomaine theory of scurvy, while utterly wrong, did mark a turning point. Doctors and scientists were finally able to move beyond observing what worked and didn’t work, and begin to ask why. The mystery was finally solved by careful science and a stroke of extraordinary good luck. While the expeditions of Scott, Shackleton and others were battling the disease, Norwegian scientists began experimenting with guinea pigs. Their good luck was that guinea pigs are the only animals other than primates which are unable to make their own vitamin C. Guinea pig research gave definitive answers on what prevented and cured scurvy, and eventually led to the discovery of vitamin C in the 1920s.

Looking back at this history of scurvy, there’s one point which stands out to me. There were many people who got it right – the locals who advised Germanicus’s soldiers, the Swedes who drank pine-infused beer, the Inuit with their diet of fresh meat, Lind with his lemons, Captain Cook who threw everything at the problem. They succeeded by careful observation, but were handicapped by not knowing why their approaches worked and why, sometimes, they failed. The unsteady progress towards a scurvy treatment, sometimes forwards and sometimes backwards, happened because the cause of scurvy wasn’t properly understood. I hope that the knowledge we have now means that we won’t fall into the same traps again, but I’m far from certain this is the case.

There is much which can be said about Cook, not all of it positive. I can’t overlook the perspectives of those whose lands he was “discovering” on his voyages. But I have to give him credit for his work in preventing scurvy, which was remarkable.

Great description! And the Spurious Correlations site -- *chef's kiss*

🤔 Fascinating! Of course I grew up KNOWING Vit C was essential for good health, but didn't realise how comparatively recently it was identified 🤷 Also, reinforces the "local knowledge" importance as to a) what they have found works and b) what is SAFE to eat in unfamiliar lands ❓