This is the last of my series on islands. I’m ending with one of the first islands that I visited, and one of the most influential on me, Tiritiri Matangi. I’ve made this article free to all, because it’s dedicated to some people who influenced me in conservation and I hope it may reach them or their families.

In the next week or so, I will be announcing some plans for next year. I’m excited about these plans and I look forward to sharing them with you soon. Because of the changes in my work situation, I’ll be offering more for my paying subscribers. I’m incredibly grateful for your support – it’s making a real difference to me right now.

At the back of my local dog park, unseen by most of the dog owners, there’s a quiet race happening. The warm weather and occasional rain mean that newly-planted trees and shrubs are sprouting away in the area my local volunteer group planted over winter. On an eroding slope, makomako trees have doubled in size, bringing hope that the soil may be stabilised. In a flat area beside the stream, plants of pukio, grass-like swamp-dwellers, are now taller than my dog, Donna. New leaves are bursting from fuchsias, coprosmas and hebes.

But the same sun and rain mean that the weeds are growing fast too – in many cases faster than the native plants. The worst are the sprouts of viciously-spined blackberry, the smothering tradescantia and choking swathes of bindweed and climbing dock which come back again and again from persistent roots. Other weeds – gigantic wild radishes, various grasses and the sticky stems of cleavers – are growing as well, but in most spots they aren’t too much of a problem.

We have working bees every month or so where volunteers remove the weeds which are smothering our plants. Donna and I contribute too. A couple of times a week, I take her for a run in this park, carrying gardening gloves, a few tools and a bag for the tradescantia, which must be completely removed or it will just keep growing. Donna races ahead of me, then stops to check I’m coming. Weeding is her favourite game. As long as the plants I’m weeding aren’t ones which might harm her, I’ll pull them out and toss them to her to catch. She thinks this is the most fun ever.

The little group I’m part of isn’t alone. Around New Zealand, there are hundreds, if not thousands, of groups which are helping to restore our environment. Wellington City alone has more than 100 groups. Each one is slightly different, but they mostly do the same three things – planting, weed control and predator trapping.

When the state of the country, or the world, depresses me, I think about these groups. I think about the many hours that busy people are giving to protect and restore the environment. Some people spend every weekend on it. Others contribute only occasionally. Some work as part of large, well-organised groups. Some work largely alone. But they are all part of a movement which owes much to the vision of a small group of conservationists in the 1980s.

I was lucky enough to know a few of these people. Today, I would like to acknowledge their role in shaping New Zealand conservation. I’d also like to acknowledge the influence that their work has had on me. Because of them, I’ve had the chance to see the way conservation in New Zealand has transformed over my lifetime. They were among the first to show me the importance of making science and environmental issues accessible to the wider public.

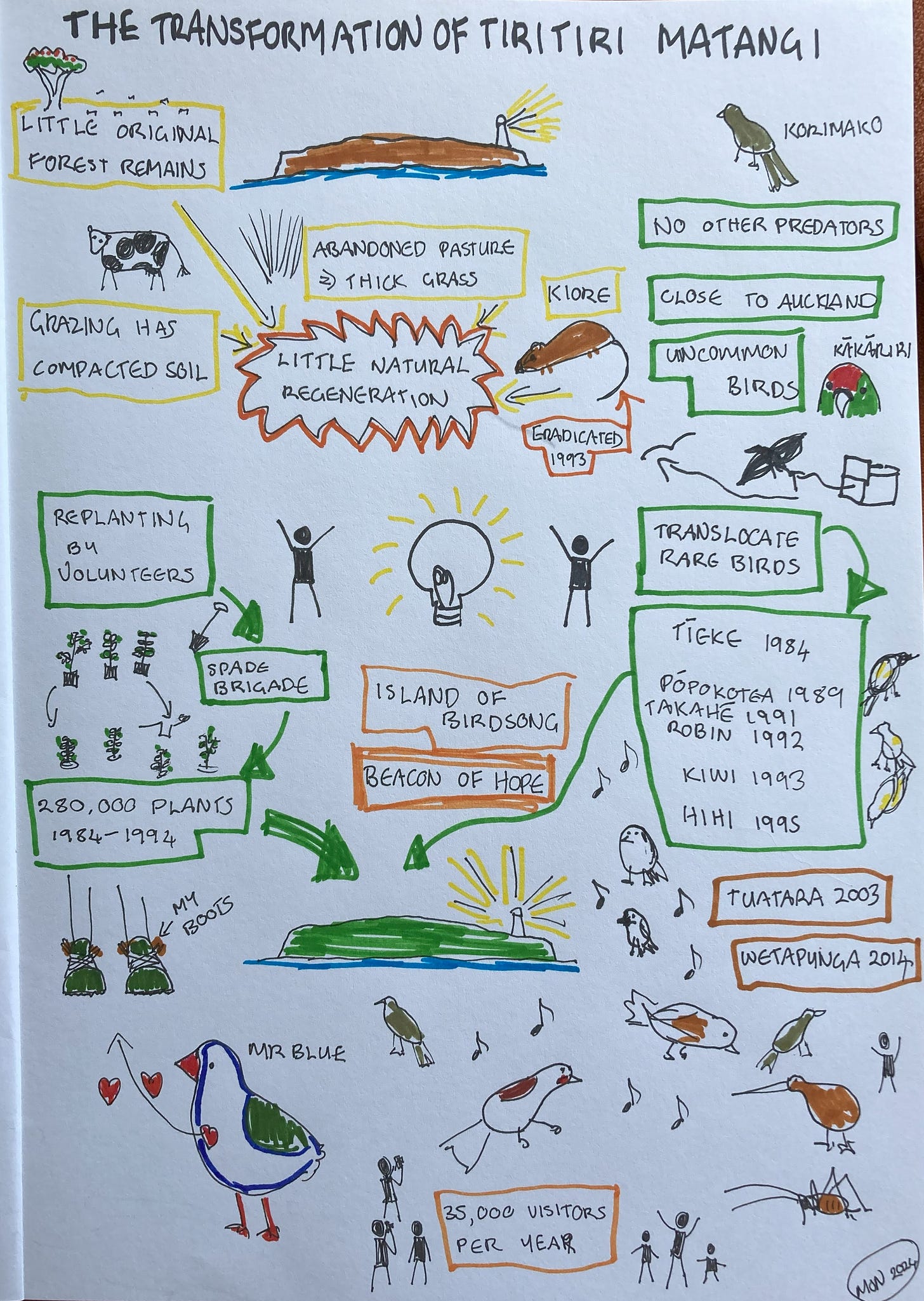

In the late 1970s, the island of Tiritiri Matangi had only a few tiny fragments of degraded forest, surviving in gullies unsuitable for grazing. The remainder of the island was covered with introduced pasture grasses, which had grown thick and tall following the removal of cattle. It had been designated as a reserve, and was largely predator-free, but native forest was showing little sign of regenerating. The grass was too thick, the soil too compacted, and perhaps there were too few seed sources for native species.

John Craig and Neil Mitchell, ecology lecturers at the University of Auckland, had the idea of recruiting volunteers to replant the island. Not only would this speed up the return to native forest, but it would also give the public a chance to participate. Along with replanting, rare birds could be moved from other islands, especially once kiore were eradicated. The Tiritiri Matangi evisaged by John and Neil was an open sanctuary where people could come and see rare species which for a century had been confined to remote island refuges visited only by a privileged few.

And so, Tiritiri Matangi’s spade brigade was formed. This group of volunteers established a plant nursery, cut tracks and dug holes in the compacted soil to plant hardy pōhutukawa trees, the first stage of restoration. They were supported by Ray and Barbara Walter, who had been the island’s lighthouse keepers. When the light was no longer needed, they became the island’s rangers, and they also grew the plants at the island’s nursery.

Among the first to become involved as a volunteer was Mel Galbraith, then a teacher at Glenfield College. Within a few years, he’d dug himself deep into the island. When the volunteers organised themselves more formally, founding the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi, Mel became the first secretary for the group. He remained an active member until his death last year.

Mel was a family friend, and I was among the hundreds, if not thousands, of occasional volunteers he took on planting trips. I’m not sure exactly when it was that we went, but I know I was still at school, so it was sometime in the late 1980s. I don’t think my efforts were a great help, but I made an attempt at digging the holes before turning to the easier task of dropping fertiliser tablets in the holes, planting the trees and then putting the soil back.

At the time, I didn’t realise how involved Mel was, but researching this article, I’ve learned that he formed a close relationship between Glenfield College and the island. His students were active participants in the island’s restoration, not only planting, but also activities such as bird translocations. When he moved to Unitec and became a lecturer there, he continued inspiring future generations of ecologists. I also learned that even before his involvement with Tiritiri Matangi, Mel was involved in setting up the Pūkorokoro Miranda Naturalists’ Trust, which built the shorebird centre at Miranda on the Firth of Thames. He was also involved with the Motu Kaikōura Trust as well as a community group supporting a number of reserves in Birkenhead, on Auckland’s North Shore.

People like Mel are the heart of community conservation and restoration projects. I was delighted to see his lifelong dedication acknowledged by the New Zealand Ecological Society at their most recent conference. He was posthumously granted the Ecology in Action award for his outstanding work in ecology, both as a professional and as a volunteer.

Mel gave me my first introduction to Tiritiri Matangi, but it wouldn’t be my last visit. Both John Craig and Neil Mitchell were among my lecturers at University, and they used to take their students to the island as well. I can remember at least one planting trip – by that time I was a little more competent with a spade – as well as trips where I learned other skills. I can remember learning bird calls and doing 5 minute bird counts in Wattle Valley. A 5 minute bird count is exactly what it sounds like: you find a spot to sit, set a timer, and record every bird you see and hear in 5 minutes.

Wattle Valley was intriguing, because I had my first insight into the complexity of invasive weed problems. There is no doubt that the Australian brush wattle which grew in that valley deserves to be considered invasive in New Zealand. However, invasiveness isn’t all-or-nothing. Some species cause more problems than others, and some species are a problem in one place and an asset in another1.

Of all the places on the island, the best spot for a 5 minute bird count is Wattle Valley. When it’s flowering, brush wattle is an excellent nectar source for native birds. However, it doesn’t flower all the time, so letting it get completely out of control, to the exclusion of other plants, isn’t a great idea. Our birds need a diverse forest to keep them well-fed. There’s another reason brush wattle is considered less harmful than some other invasive trees. It doesn’t tolerate shade, so in some environments, as long as it isn’t burned, it is eventually replaced by other species. This is what will happen in Wattle Valley eventually – in fact, it may have happened by now, since I was doing bird counts there in the early 1990s.

In all my visits to Tiritiri Matangi, my most memorable moment was the time I met Mr Blue the takahē. Mr Blue was one of two male takehē introduced to the island in 1991. Their introduction was an experiment to see how this bird, which had been reduced to a small area in the Fiordland mountains, would cope with Auckland’s warmer conditions. The experiment had some unexpected results – the two paired up and built a nest. When they were given an artificial egg, they incubated it, and when given a real egg, they hatched it and cared for the chick.

Mr Blue had been hand-reared, and was totally fearless with humans. In fact, he was beyond fearless – he was downright pushy. In those days, my tramping boots were older than I was. They were scuffed green leather, with brown sheepskin at the ankles the only concession to comfort. Mr Blue liked the look of them, so he marched up to me, grabbed one boot in his claws and made a vigorous attempt to separate it from my leg, with my foot inside, by pecking at my shin. I was left with a substantial bruise and I was so proud of it. Attacked by one of the world’s rarest birds! How many people could say that?

Since those days, I’ve only been back to Tiritiri Matangi once, and it was a different place. There’s a regular ferry, less than half an hour from Gulf Harbour at the tip of the Whangaparāoa Peninsula. It’s internationally recognised for its success. Visitors from around New Zealand and the world come to see the abundant birdlife. And many thousands of people like me treasure the island because they played a part, however small, in its success. Thank you, John, Neil and Mel for giving me that opportunity.

This is putting aside the point that people value different things, so one person can see a weed problem and someone else can see a scenic delight.

Thank you for sharing all the hard work that is being done to restore the island. It is so sad to see that so many islands around the world have seen a similar faith with deforestation and destruction. I applaud all the hardworking people for all the work they put it. They are the real heroes.

While they are a newish feature, I enjoy your diagrams and hope you include them regularly.